Where Fashion & Robotics Are Starting A Quiet Revolution In The Way Clothes Are Made

Fashion & Robotics combine at the University of Arts Linz,

starting a quiet revolution in the way clothes are made

Words by Farah Shafiq

“In Linz, the opportunity for collaboration and innovation is right here,” says Christiane Luible-Bär – a professor operating at the heart of the Austrian city’s creative-industrial energy. Luible-Bär co-heads Fashion & Technology at the University of Arts Linz, a relatively new department founded in 2015, which weaves fashion amongst Linz’s thriving hub of tech expertise, focusing on sustainable solutions above all.

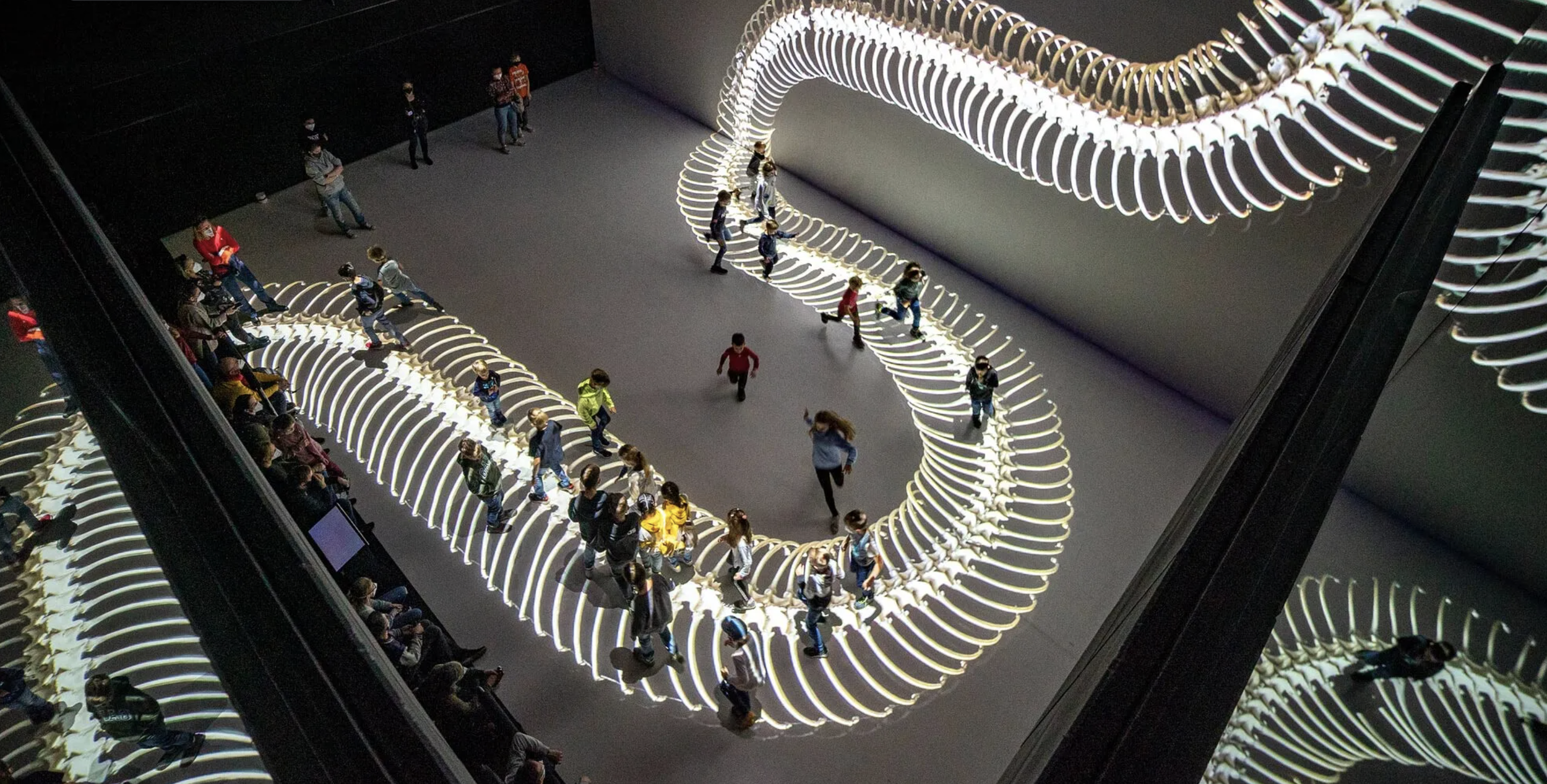

Image from ars.electronica.art

Linz is perhaps best known for Ars Electronica, a “festival for art, technology and society” founded in 1979, which takes place in early September each year. The fascinating performances, lectures and exhibitions showcased there are designed to provide a platform for innovation, to inspire and drive forward conversations and ideas, with circularity emerging as an overarching theme in recent years. It’s a raison d’etre that comes naturally to the city, and is what first drew Luible-Bär – and Looms – towards Linz.

Images from ars.electronica.art

Luible-Bär works closely with colleagues: Johannes Brauman, who is responsible for the creative robotics lab; Werner Baumgartner, the leading expert on bacteria; and their team members including Emanuel Gollob, Miriam Eichinger and Agnes Weth. Here, we explore Linz through the lens of their research in material innovation, learning more about the collaborative spirit and creative outlook for sustainable futures.

Set the scene for us, what’s it like in Linz? Disrupting the status quo

I love it here. As well as the arts that stem from Ars Electronica, there’s a lot of innovative industries: from artificial intelligence to research institutes. From the technology side, it’s a very interesting place. Research wise, the companies here contribute a lot in terms of funding. And, with such a short distance between everyone, it creates a very special energy.

There are also many initiatives within Linz; its aim is to gain recognition as a startup city. It has a similar energy to Berlin, where they make space for startups – and the location of our department is right at the heart of this. For our students, it’s really motivating. For example, three floors down there’s an incubator for startups with funding who they can work with and take inspiration from. The whole city is focused on fostering this spirit.

How does the department contribute to this drive for innovation?

When myself and Ute Ploier (designer and head of department) thought about what would work for a fashion education in Linz, it made sense to focus on important future technologies – because, fashion is in flux, and very much on the lookout for new, more sustainable processes. When we started, in 2015, it was the time of smart textiles and 3D printing, so these were the first areas we focused on. It was more of a technology centre, where we assessed the potential of these new technologies.

Eight years later, we have evolved our approach, almost flipping it entirely. Now, fashion leads, and the projects ‘ask’ for certain technologies. Masters students specialise even further, honing in a particular technology in order to innovate.

We don’t focus on one specific technology in the curriculum, we look at several, linked to the industries here: robotics, programming, 3D modelling, smart textiles, knitting and weaving.

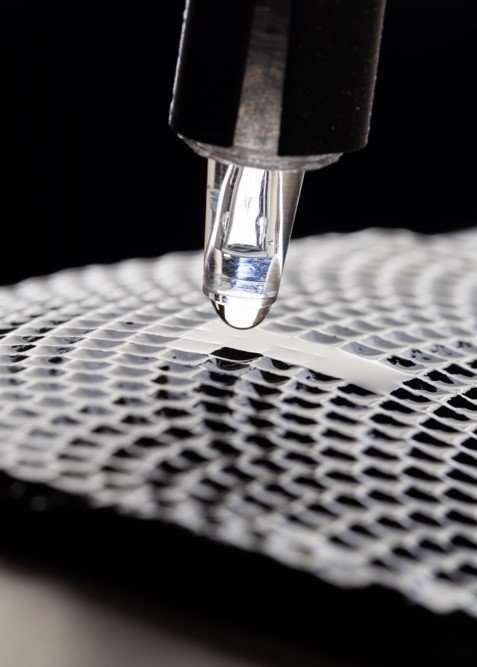

Images by Jürgen Grunwald

More recently, you’ve led an artistic research project combining bacteria and robotics to grow new fabrics –tell us a little more about this?

Before coming to Linz I worked in a research laboratory in Switzerland on various digital projects, which led me to robotics. Johannes Braumann and myself started to think about how we could work with robots here, and so the Fashion & Robotics ‘Grow Whole Garments’ project was born.

Students were very much interested in incorporating bacteria into their work: some growing their own bacteria-based materials, others using bacteria for the dyeing process [see Looms interview with Julia Moser for more on this, here]. To grow materials, we found that the bacteria need a 24-hour nutrition agent – and this is where the robot comes in, to feed and monitor the bacteria. It turns out that the robot is actually the ideal tool to take care of these growing organisms.

That’s why, as well as testing bio-based materials in architectural contexts, Material Cultures examines how they could be integrated into the complex networked system of politics and economy that surrounds the construction industry in the UK – a sprawling ecosystem of labour, supply chains, agriculture and land-use. If materials are to be grown here, reducing the carbon costs of global material transportation, it will depend on agricultural reform and combining crops for construction materials with other competing crops and land-uses, explains Gormley.

How easy is the bacteria to work with?

There are certain rules that have to be followed when working with bacteria. The Institute of Biomedical Mechatronics, led by professor Werner Baumgartner, is a project partner of Fashion & Robotics and we work closely together throughout. Baumgartner says that the bacteria we use “is like what you have in the bathroom” – so it’s not very dangerous, but you still have to take care with it.

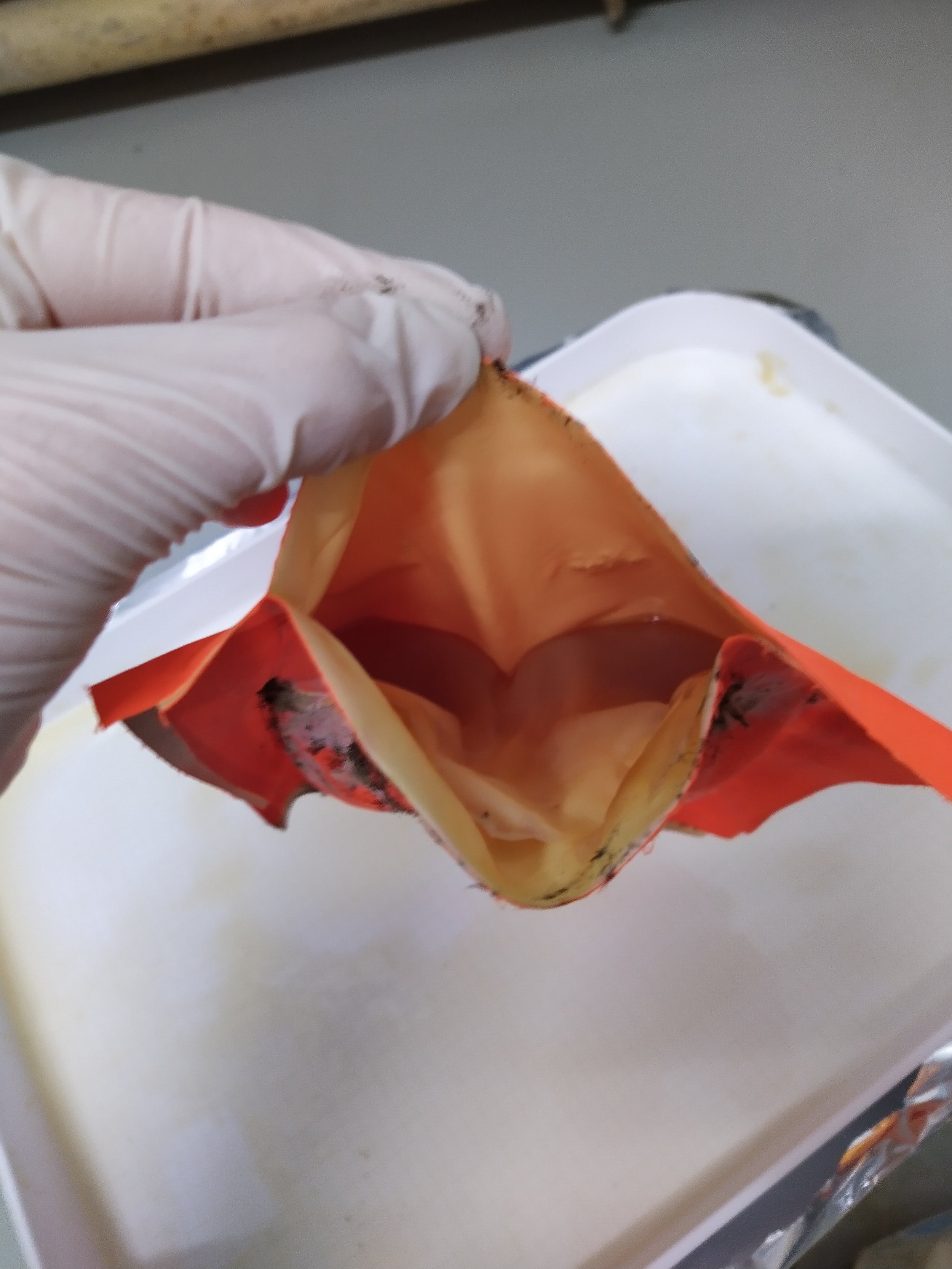

To grow the bacteria into material, it needs to be fed oxygen and sugar water. As long as the bacteria is alive and the material is growing, it has to be sealed up, so that it doesn’t contaminate anything. We do this growing process in a separate lab, then when the material is ready, we move to work with it in a more open space.

When it reaches the desired size and shape, the material can be harvested. For this, it has to be cooked to stop the growing process, then ironed to maintain its form, followed by various finishing treatments so it doesn’t dry out too much and remains malleable and durable. There are a few stages, but it’s not rocket science!

Images by Miriam Eichinger

What does the future look like for these sustainable materials?

There’s no question that bacteria-grown material is absolutely possible at scale, it just needs further development. So far, most of our projects have been more artistic and experimental – but now we know this particular method of bacteria-grown material is possible, we want to move towards realisation and industrialisation.

From a commercial standpoint, bacteria-grown material is still in the research phase. The timescale is a factor, it needs 10 days to two weeks to grow, so it obviously can’t compete with the fast fashion industry. What we’re hoping to work on next is scalability; how much can we produce, how can we expand the robotics aspect to automatise the process, and how can we better control it.

To create a quality garment, it needs time – and that has to be reflected in the price for a viable business. The problem is, we’re not used to this time and cost requirement any more, because of fast fashion. So, I see bacteria-grown material starting in high fashion, where a more expensive product is expected, and evolving from there.

There’s a change in mindset coming from the consumer now, too. I strongly believe that people are willing to pay more for products that are made from true sustainable materials, those that can be composted at their end of life. This change in mindset and market will take a few more years, but it will happen. If you look at the likes of polyester and cotton, they are so problematic – we need new materials.