Aspirational Eco-Homes & The Architects Who Live There

The ideas behind the buildings that make sustainable living look seamless

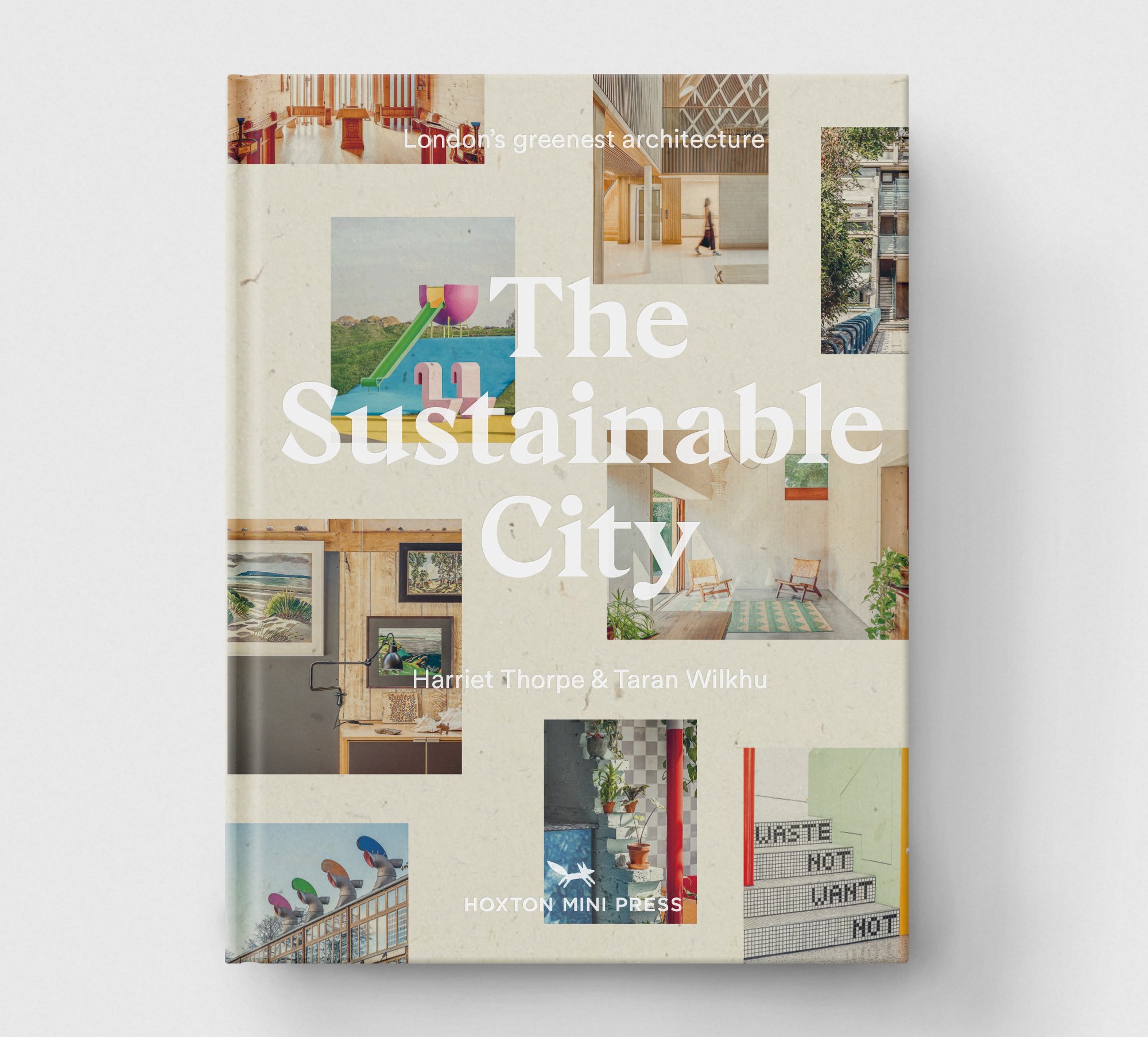

Words by Harriet Thorpe. Images from The Sustainable City by Taran Wilkhu, courtesy of Hoxton Mini Press

As our global population grows, city-dwelling does make sense when it comes to living more sustainably – so, if you’re reading this from your urban base, know that there’s plenty of potential. We will get into some specifics in this article, but let’s start with a broader overview…

Cities encourage a shared and more efficient use of the things that take a toll on our environment, from transport to heating. Plus, the population density of cities helps to keep the countryside green, as it should be. What is unsustainable however, is how cities are growing; globally that means slums and pollution are increasing, among many other issues. It’s interesting to think that cities occupy just 3% of the world’s surface, yet account for about 70% of global carbon emissions and consume over 60% of global resources – there’s clearly work to be done.

So, what exactly are we aiming for? According to the UN, a ‘sustainable city’ must provide firstly the basics: safe resources (like clean water), functioning services (like paths and roads) and affordable housing (shelter). Then, it should also present dynamic opportunities, shared prosperity, social stability and make environmentally-friendly living an easy choice for its citizens. And, it should actively help to repair, enhance and contribute to the regenerative health of our Earth.

The case-study city

It’s a tall order, but there are certain cities around the world that are rising to meet that criteria. Let’s look at London, for example. There are progressive positives to note: see its ‘Ultra-Low Emission Zone’ tackling vehicle pollution; its bicycle-sharing schemes; efficient public transport system; and 3,000 parks across the city. However, it’s clear that there is still much room for improvement. Buildings are wasting energy leaving 398,000 London households in ‘fuel poverty’; the city generates vast amounts of waste (seven million tonnes each year); and 16% of major roads in London exceed the legal limits for nitrogen dioxide, one of the main contributors to air pollution.

Over the last couple of years, I have been exploring the topic in detail, and in 2022 distilled these investigations into a book: The Sustainable City (published by Hoxton Mini Press). In it, we hone in on how good architecture and design can help solve some of the problems that cities are facing, and meet key people who are part of that process – from architects to residents, all making the city a cleaner, healthier, greener and happier place to be.

The buildings featured in the book approach sustainability in many different ways; from low-energy housing estates that reduce energy bills for residents; to beautiful timber buildings combining carbon-negative design with craft; unloved Victorian factories carefully preserved and repurposed into modern workspaces; a Brutalist council building reborn as a 70s-inspired hotel; plenty of warm, healthy and inspiring eco-homes making life easier for their inhabitants.

Three inspirational eco-houses

Of all the types of buildings featured in The Sustainable City, the ones that seem to captivate people the most are the eco-homes. Sometimes urban living can feel unsustainable, because many decisions feel beyond our control, especially alongside the busy lives that city-dwellers tend to lead. Yet the eco-homes featured in the book make sustainable living look seamless – with inhabitants in control of their carbon footprint, from saving energy, to growing vegetables.

The eco-homes below have each spotted opportunity amid forgotten, derelict and unused plots of land in the city. Like puzzle pieces their forms are unique and adapted to the size of their sites and the lives of the architects who live there. They are characterful and have unique identities reflective of the materials and low-energy building techniques they adhere to; and they all empower their inhabitants to live more sustainable lives that are comfortable and healthy. Importantly, they re-imagine the type of place a city could be.

Justin Bere’s Passivhaus home

In Newington Green, behind a terrace of four Grade I-listed houses, architect Justin Bere has designed a ‘Passivhaus’ fortress forto sustainable living. The ‘Passivhaus’ certification ensures the lowest possible energy use through design, materials and harnessing the natural energy of the climate. Bere was an early adopter of the German certification, and has built his career as an expert in designing to its rules. His own experimental home built in 2002 has thick masonry walls and triple-glazed windows to keep it sealed as tightly as possible to stop heat escaping and drafts entering, while shading systems keep the interior cool in summer. The layered arrangement of the house creates space for green roofs, which provide summer shading and a little haven in the city for plants, insects and birds.

Hugh Strange’s resourceful base

Meanwhile in Deptford, architect Hugh Strange’s single-storey, two-bedroom house is built in a disused pub yard. Another peaceful urban escape, the 75-square-metre house built in 2010, brings many different ideas together under one roof, from the reuse of a neglected urban site, to the cross-laminated timber structure, and the passive and renewable approaches to energy use. (seems here we need few more details to make it less generic like what sort of renewable energy etc like the one below) The house has also enabled him to live a more sustainable life in the city – reducing his commute down to a short stroll across a courtyard, and allowing him to better connect with his family and nature.

Sarah Wigglesworth’s off-grid hub

Exploring the possibilities of living off-grid in the city, architect Sarah Wigglesworth’s Kentish Town house, built 2001, uses low-tech materials that are easily recycled, biodegradable and/or made of low-embodied carbon or waste products; all used in a highly technical way. For example, straw bales, after which the house is nicknamed, provide excellent insulation. The 550 bales are protected by a transparent polycarbonate plastic rain screen, with a layer of perforated metal and insect mesh to keep them both dry and ventilated. Elsewhere, sandbags, railway sleepers, recycled concrete-filled gabion baskets and even quilted-fabric cladding have stood the test of time. Based on thermodynamic and aerodynamic science, manually operated, shuttered air vents on the ground floor allow air in, which rises through the house, to a tower that draws air out – so Wigglesworth can control the temperature of the building just like a layer of clothing.

The Sustainable City always set out to be optimistic and show up with solutions that are in practice, built and a reality. It is as much about the architecture, as it is about people and ideas. Our hope is to inspire that confidence, curiosity and joy in the future of more sustainable cities.