The Enchanted Valley

Ecotourism and inequality in the forests above Rio de Janeiro

Words by Imogen Lepere. Images by Mark Rammers

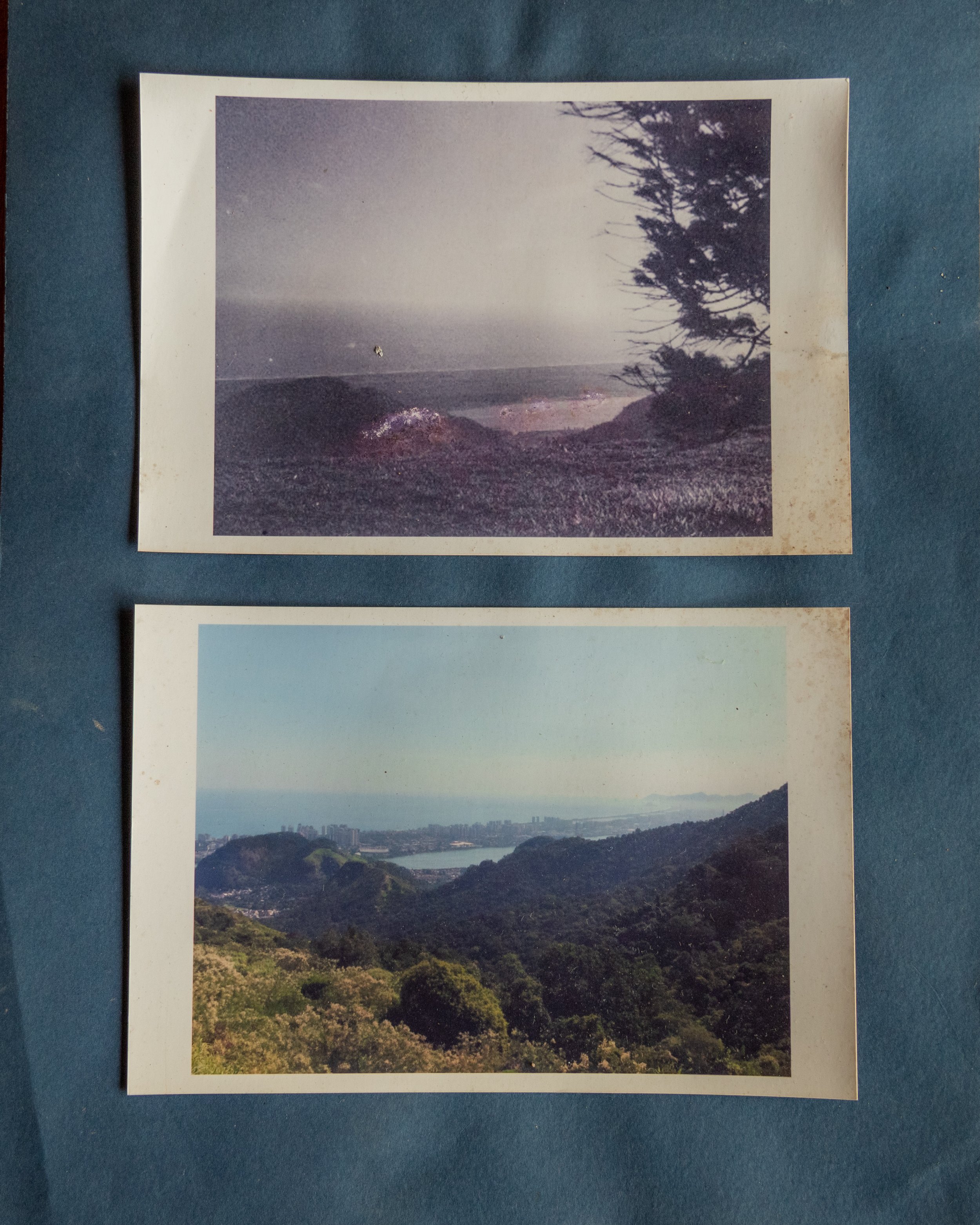

As Otavio Alves Barros makes coffee, I look at the religious painting on the wall. It reminds me of Rio de Janeiro’s Christ the Redeemer statue, which is just a 30-minute drive away through the forest of Tijuca National Park. Although it’s late morning, the little kitchen is in deep shadow; mist rolls down from the mountain crest just above us and the lights keep flickering out.

“The energy companies don’t care about the Vale Encantado as only 100 people live here,” says Barros, who is a sixth-generation resident. “So we’ve installed solar panels. They don’t provide enough power for everyone, but they do help with the bills.”

Although we can see the gleaming skyscrapers of Barra, one of Rio’s most upscale neighbourhoods, it feels as if we’re in a different world. The wide boulevards have been replaced by dirt alleys narrow enough to touch the walls on either side and every spare scrap of land has been transformed into a terrace for citrus trees and organic vegetables.

This tumble of buildings is known as ‘Rio’s most sustainable favela’ (although the term ‘community’ is considered more politically correct these days) and residents take protecting the Atlantic Forest that surrounds them seriously. Aside from solar panels, they also have their own anaerobic sewage system, drinking water filtered from mountain streams and a supply of biogas made from food scraps – all funded by a community cooperative and installed by Barros himself. And now they’re going one step further with an ambitious eco-tourism project that they hope will protect the environment, while also generating some much needed income.

“The aim is to live in harmony with nature and work together to empower every person equally through ecotourism. There’s no public transport here and we only have 10 cars between us, so at the moment if people get jobs in the city they have to leave – very few young people are left.”

Barros leads the way to the heart of the project, a room with sweeping views over the valley and ocean beyond where lunch is served to hiking groups. The building cost 60,000USD, half of which was donated by Dutch philanthropic institute, Porticus, and the remaining 30,000USD raised by locals pooling their savings and working with bakery chain, Le Pain du Lapin over several years.

“They donated leftover bread which we turned into melba toasts and sold back to them.” Proudly he shows us around the room: packing crates serve as window seats, wooden boxes from a market are lamp shades and floral bunting shifts in the breeze.

Barros leads the way down through the village to show us the sewage system he and some other residents learned about on YouTube and fitted themselves. Previously, the septic tanks provided by the government were seeping into the drinking water.

“Voting is mandatory in Brazil but we’re such a small community, it's not worth it for politicians to put in much effort so we’ve been left behind – until we started the project there were no paved roads, no street lights, no sanitation. See those stairs?” He points to a stone stairway leading sharply down the mountain. “They were supposed to have handrails, but some of the parts never came and the bits that did rotted before the rest were delivered. All the infrastructure we have, we’ve made ourselves.”

Although the community has been working on the project since 2005, receiving regular income from ecotourism may still be many years away. Brazil is a country with growing inequality, exacerbated by Covid as well as the impact of climate change and a tax system that favours the mega wealthy. Currently, the six richest individuals – all men – have the same wealth as the poorest 50% of the population (around 100 million people). Building materials are increasingly expensive and the community is struggling to raise the funds to see the project to completion. The room myself and photographer Mark Rammers sleep in remains half built, as does the restaurant’s kitchen.

When completed, the vision is to have several bedrooms so guests can spend all day discovering the valley’s hiking trails with a local guide, stay overnight and enjoy meals of locally grown vegetables in the restaurant. This will create jobs for numerous locals – cleaners, cooks, guides, drivers – as well as generating income that will go towards maintaining and developing the village’s sustainable infrastructure.

“One of our dreams is for the Vale Encantado to become a blueprint for nearby communities where they can learn how to become self-sufficient without diminishing nature’s resources,” says Barros. “Listen,” he gestures outside. The only sounds are the birds and rain pattering on the banana trees. “That tranquility is what I want to preserve for future generations and one of the only ways to do that is to generate income from it. If people understand its value, the forest will still be standing long after I’m gone.”

To visit Vale Encantado, message Otavio on Instagram @vale_encantadorj