The Untold Truths of the Deep Sea

Rhiarna Dhaliwal’s critical look into deep sea mining

Words by Harriet Thorpe. Images by Rhiarna Dhaliwal

“How we access the deep sea – depict it, draw it, visualise it – has an effect on our relationship to it, and if we care about it or not”

The deep sea is a territory that multidisciplinary designer Rhiarna Dhaliwal compares to space. It is vast – from 200m deep, where light disappears, to over 10km down. Its true depths are unknown – only 0.0001% of the seafloor has been explored because it is so challenging and dangerous for humans to reach: pitch black, with crushing pressure and cold temperatures.

This is just the type of territory that intrigues Dhaliwal. While studying architecture at the RCA in London (class of 2019), she found herself drawn to those hard-to-reach, large-scale territories often considered dystopian or ‘other’. She set herself the challenge of using her design skills to connect these realms to our everyday lives – as a means to communicate that, while they may seem distant, they are crucial to keeping our earth in environmental balance.

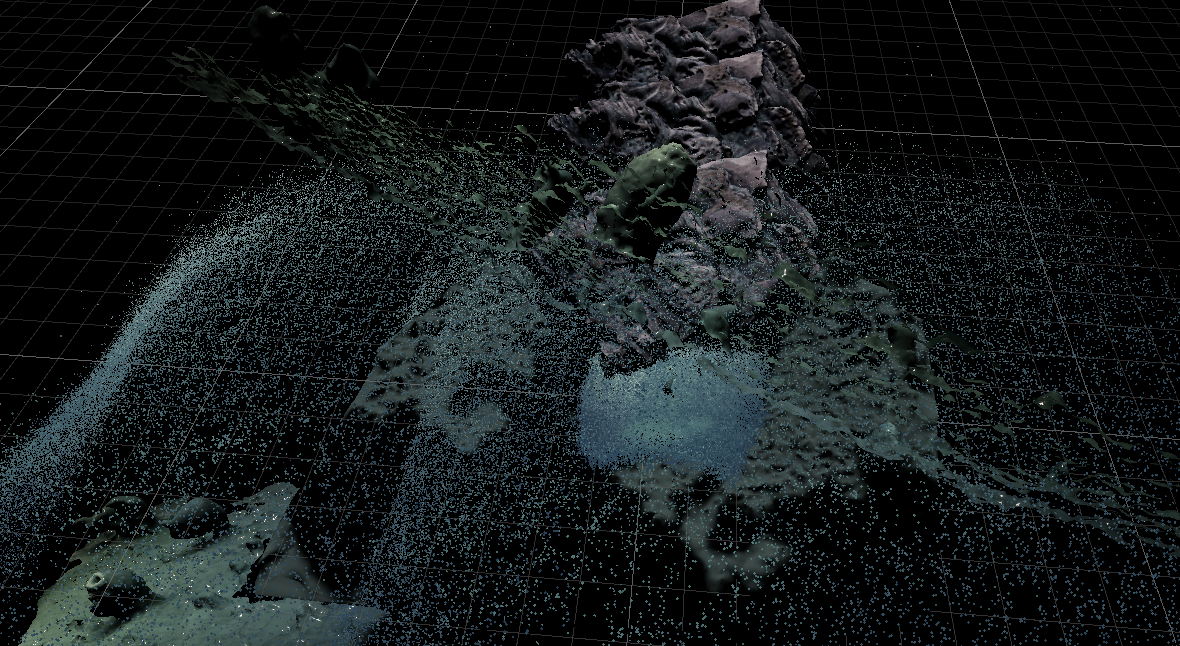

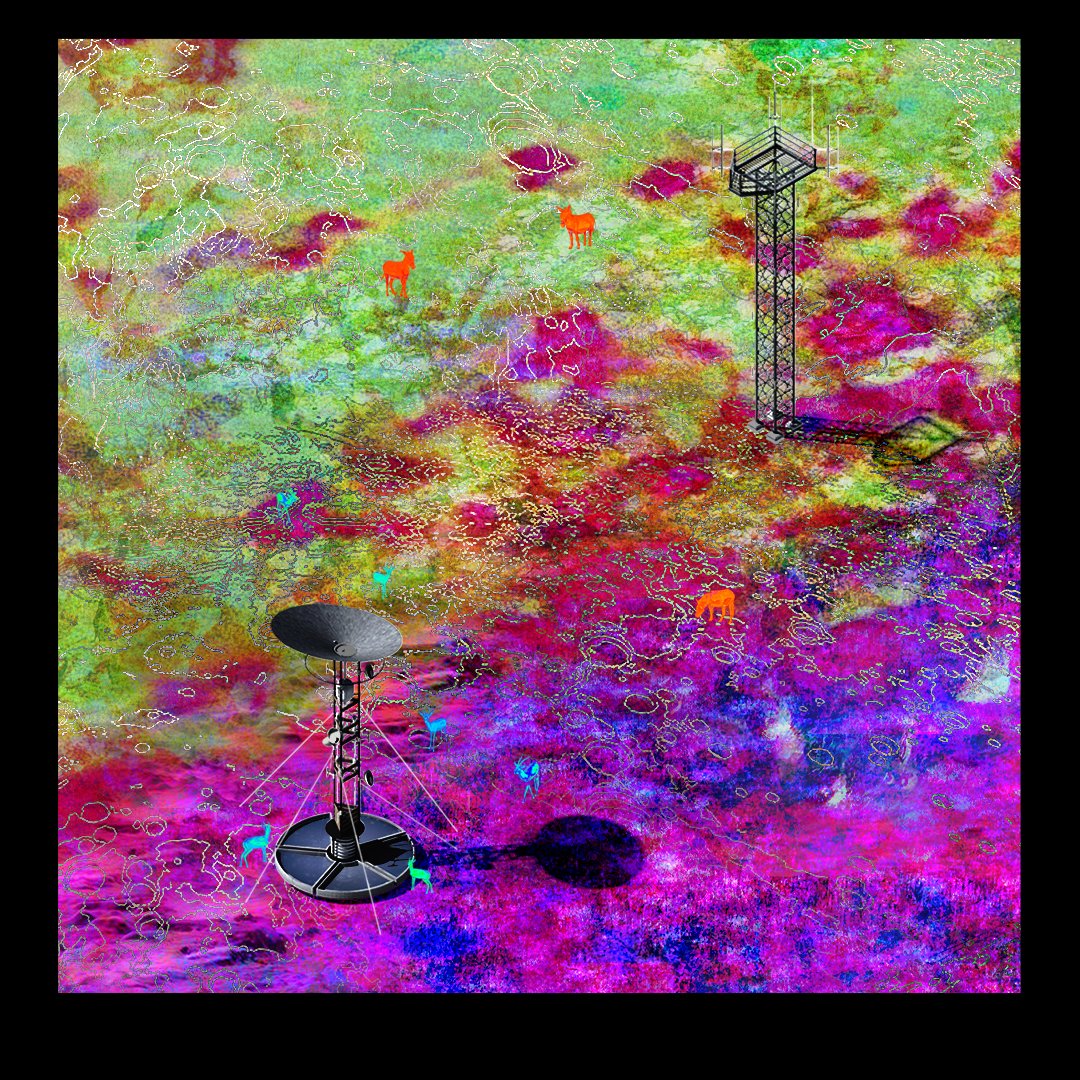

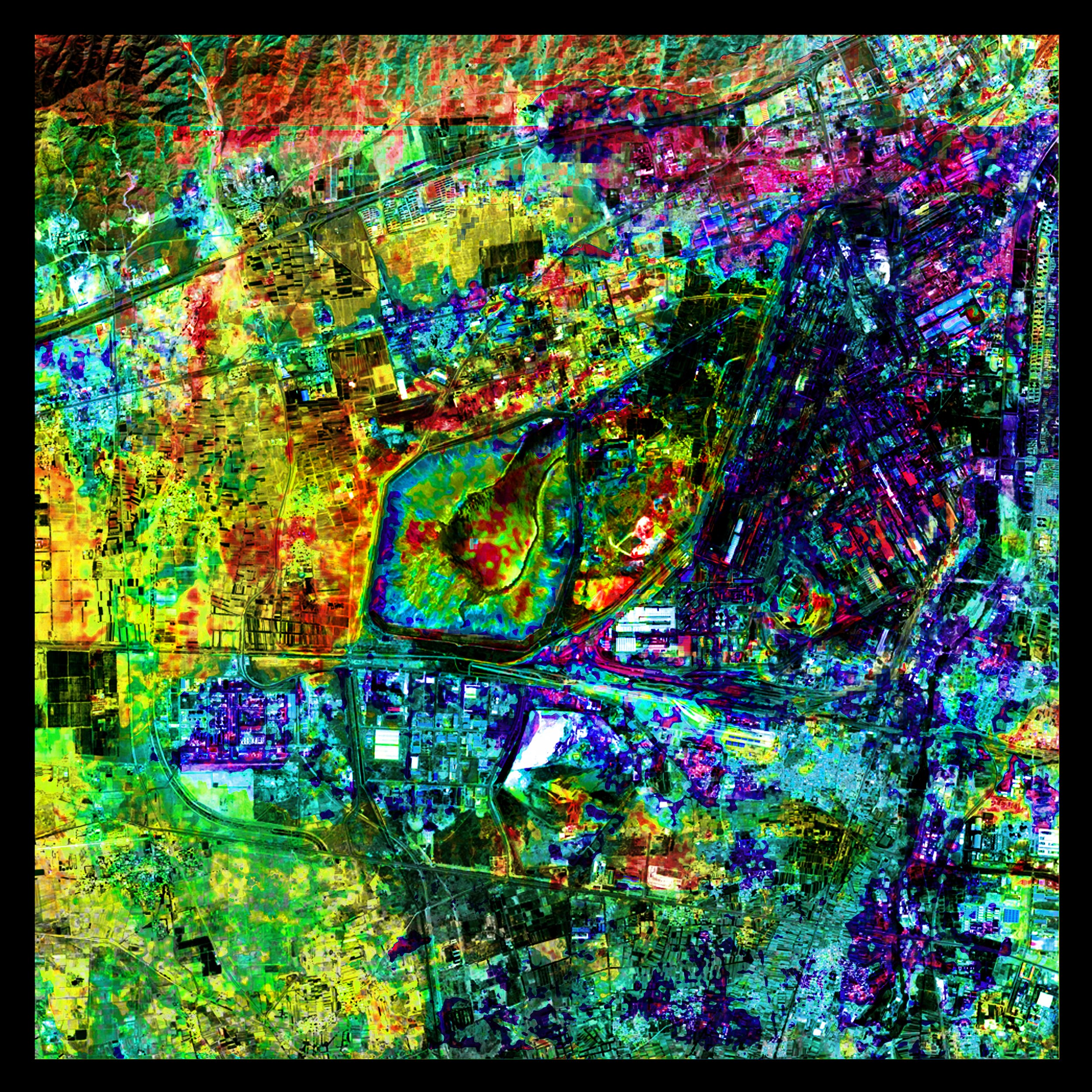

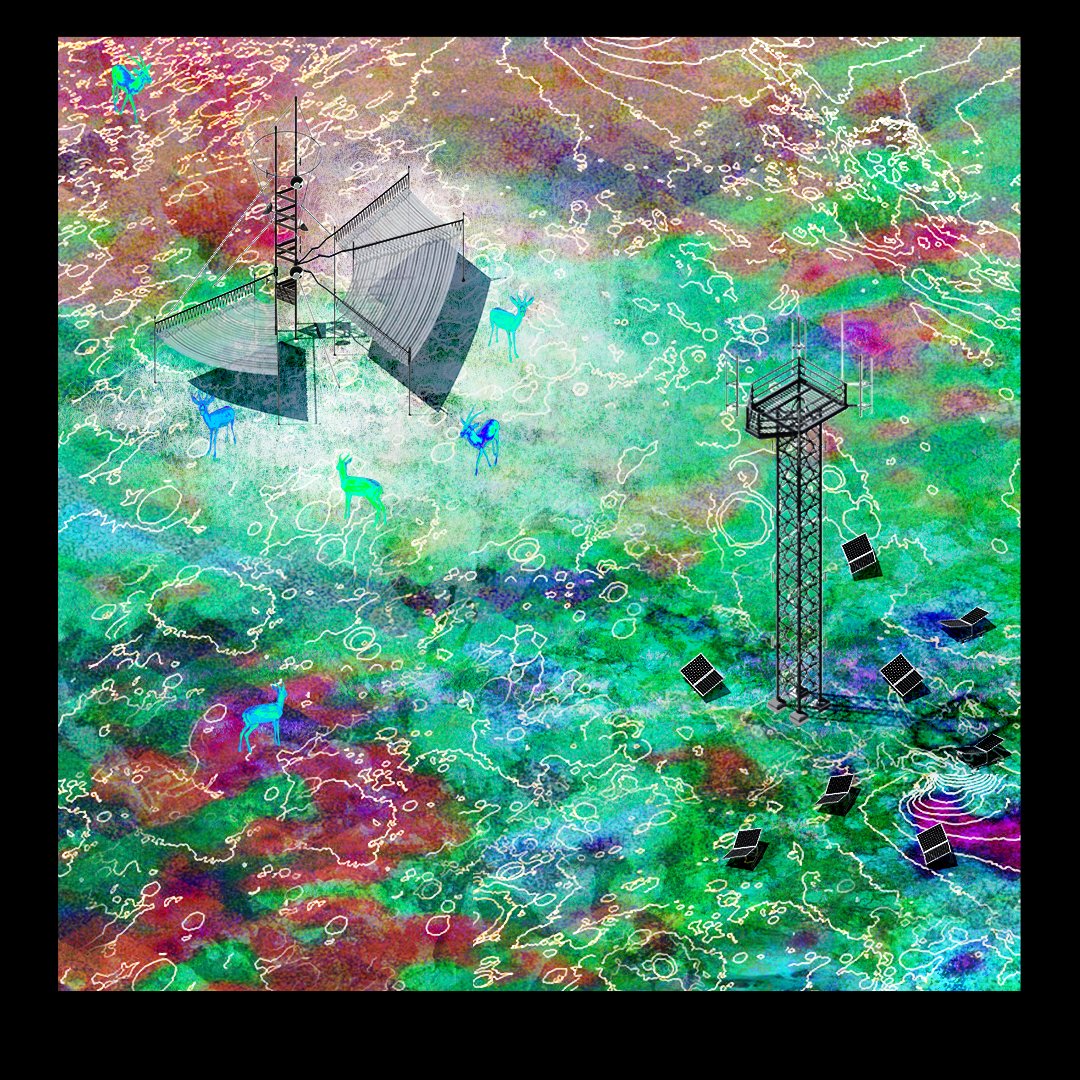

Designer Rhiarna Dhaliwal renders the delicate deep sea ecosystems using infographics, game engine software and illustration.

As a participant in the Design Researchers in Residence programme at the Design Museum (2022-23), Dhaliwal took a deep dive 4km down to the sea floor of the ‘abyssal zone’, where trillions of polymer titan nodules (clumps of minerals such as cobalt, manganese and nickel the size of potatoes) gather. There are fields of these, which take millions of years to form around tiny fallen objects such as shells or teeth, forming anchors for delicate bio-diverse ecosystems of microbes and bacteria, glowing sharks, armoured snails, sea cucumbers, sponges, nematode worms and plenty more characters yet to be discovered, all able to thrive where humans can’t.

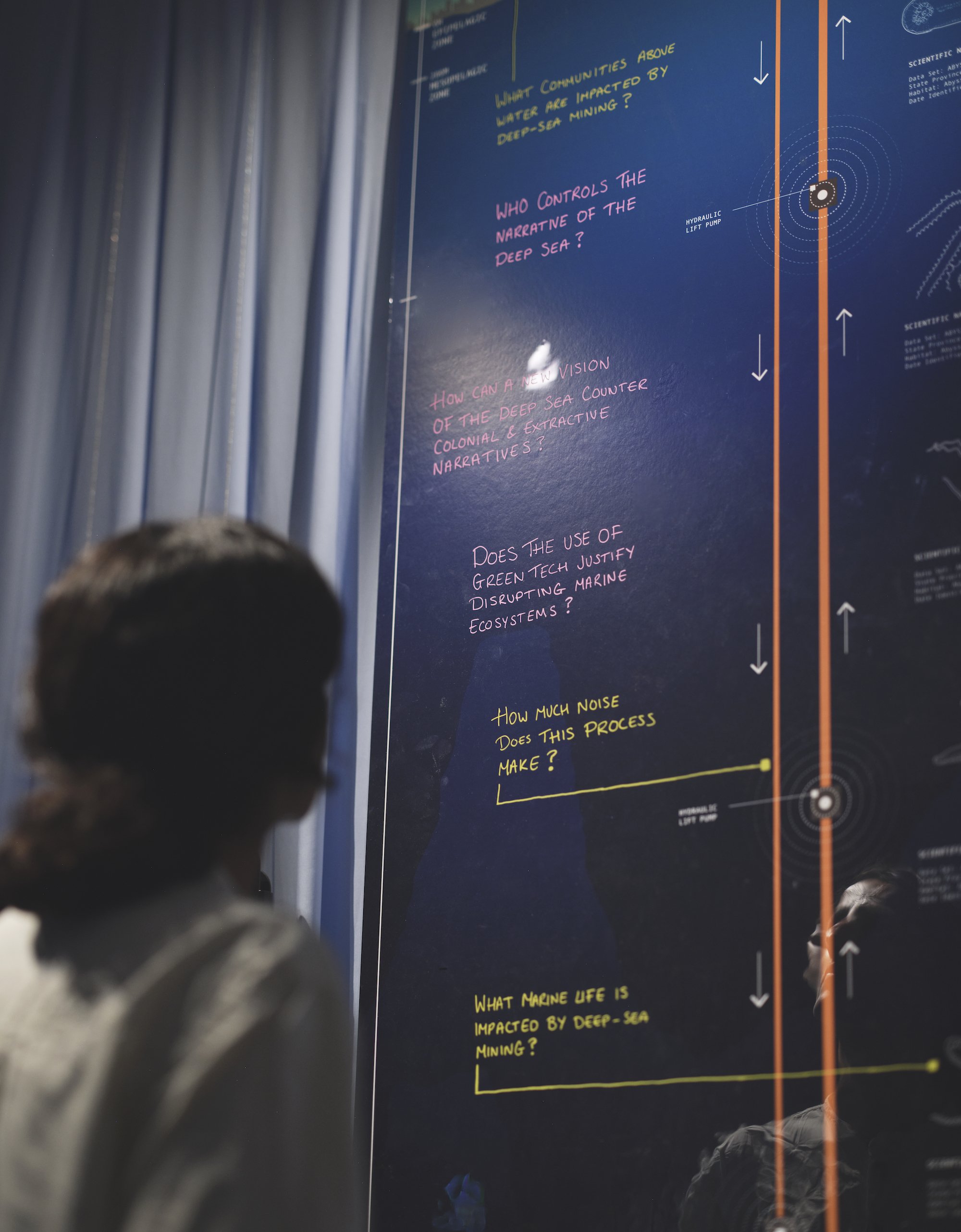

These fields are currently attracting mining companies for their usefulness to the technology industries, in particular the growing renewable or ‘green’ energy sector for wind farms and solar panels. Yet imagine the violent impact mining has on land – it has the same effect under water and would destroy the environment and its habitats. As part of her research process Dhaliwal posed the question: “Does the use of green tech justify disrupting marine eco-systems?”

The answer is under debate. The UN Commission for Human Rights, politicians, scientists, Indigenous groups and environmental activists are currently campaigning to place a moratorium on deep sea mining on the grounds that it is unnecessary and could cause unknown and irreversible impact to the environment and the global climate. Yet talks at the regulator International Seabed Authority (ISA) based in Kingston, Jamaica, in July 2023 concluded without resolution, with plans for further discussion in 2024. While some countries are against deep sea mining — including Germany, Spain, Chile and New Zealand — others, including Norway, China and India, support it.

With decisions pending on the world stage, Dhaliwal’s goal to connect the deep sea to a public audience at the Design Museum in London was all the more urgent. Yet how do you connect people to a place that is so inaccessible and has never been seen with a human eye? The deep sea has only been accessible via machines from the late 20th century. Academic studies are patchy and limited due to challenging conditions. Humans rarely venture down, and when they do, it is up to rovers with lenses and bright lights to illuminate and frame the space.

“How we access the deep sea – depict it, draw it, visualise it – has an effect on our relationship to it, and if we care about it or not,” says Dhaliwal. “If you can’t personally access that space, images have a really big impact.” However, accessible images thrown up by Google and AI image generator Dali of the deep sea depict dark, barren landscapes that look empty. “Extractive narratives are able to be produced about this landscape because there are not many people vocalising how this environment exists. It aids the reasoning that we can extract because it won't impact us, because nothing exists there.”

“Does the use of green tech justify disrupting marine eco-systems?”

Critiquing the intersection of data, images and space is where Dhaliwal is developing her expertise as a designer. Within the all-female collective Xcessive Aesthetics, founded in 2019, she explores data and alternate realities through spatial design and digital tools. She also teaches a new bachelor’s design studio, Studio Digital Native at Design Academy Eindhoven, which seeks to ‘rethink the infrastructures of technology, surveillance, and of media culture, in their relation to physical realities and public space.’

A key question that arose from Dhaliwal’s early exploration was: “Who controls the narrative of the deep sea?” She discovered much of the technology used to explore the deep sea by the National Oceanic Observatory is developed by NASA or the military, conjuring parallel narratives between space and the deep sea, both starting to point to colonialist approaches.

Rhiarna’s RCA thesis project explored rare earth mining in Inner Mongolia. In her quest “to really look at everyday objects and question how they are made and where they come from,” she traced the minerals that end up in electronic devices such as mobile phones from source, to extraction, to manufacture.

“Who controls the narrative of the deep sea?”

In response, she decided to create her own narrative, translated and transformed from scientific research and super numerical data into Extracts of the Abyss, a display at the Design Museum, London. A video designed with game engine software showed the projected effects of mining on the deep sea; alongside an iPad showing a data set published by the Natural History Museum, focussing on the 4.5 million km2 Clarion Clipperton zone in the Pacific Ocean, the main site of contention for deep sea mining. A to-scale infographic compared the deep sea to the (correspondingly tiny) London skyline, alongside ships and machinery the size of small towns required for deep sea mining. A series of visually captivating maps and diagrams presented everything from potential mining sites, to materials in a polymer nodule and how they are employed in a hard drive or an EV battery.

“I want people to interrogate the world that exists around them, to really look at everyday objects and question how they are made and where they come from”

While data can tell one story, there are always other stories — such as those told by Indigenous communities, who have lived in the Pacific Ocean for centuries, existing far from digital realms. Deep sea mining could drastically alter the ocean ecosystems on which these communities rely for their livelihoods and culture. By building up an understanding of the deep sea, Dhaliwal hopes that people will begin to think more about the ocean as an ecosystem that we are all part of. “I’m trying to put forward an alternative narrative to the public, to consider other spaces that are experiencing stories of extraction, ecological damage and violence. How do we engage in a more critical understanding of them? How can we have more empathy towards people who live there? How are our life choices impacting those people?”