3 Explorers In Our Material World

Ethical cremation urns, mushroom walls & reactive plastics

Words by Farah Shafiq

When Looms visited the Material Matters exhibition as part of London Design Festival 2023, we were struck not only by the amount of chairs made from every material you could possibly imagine, but also the breadth of innovation and out-of-the-box thinking currently taking place in the world of design.

Have you ever considered, for example, whether something like a mushroom might make for effective soundproofing? Wondered how UV radiation might be affecting our DNA, and how we can become more aware of and responsive to it? Or, thinking in a completely full-circle mindset, whether the vessels that might one day hold our ashes could align more peacefully with the earth?

As ever, the overarching question remains as to whether these explorations do enough to make a significant impact. There’s debate as to whether there are any real solutions, or whether these efforts are merely trade-offs. Whether the ‘circular’, ‘eco’ and ‘sustainable’ materials and processes in use are just less bad than their alternatives. Is there hope for something genuinely better?

Discussion of the above is essential, and the conversations we’ve had along the way so far are promising. The design community is not self-congratulatory, but neither is it downbeat or defeatist about the enormity of environmental challenges. Instead, the industry seems wholeheartedly committed to further investigation and in doing so, making some cool discoveries that are truly circular.

Below, we speak to three changemakers about projects that stand out, their creativity and the potential of what can be achieved when we rethink our approach to the material matter that surrounds us.

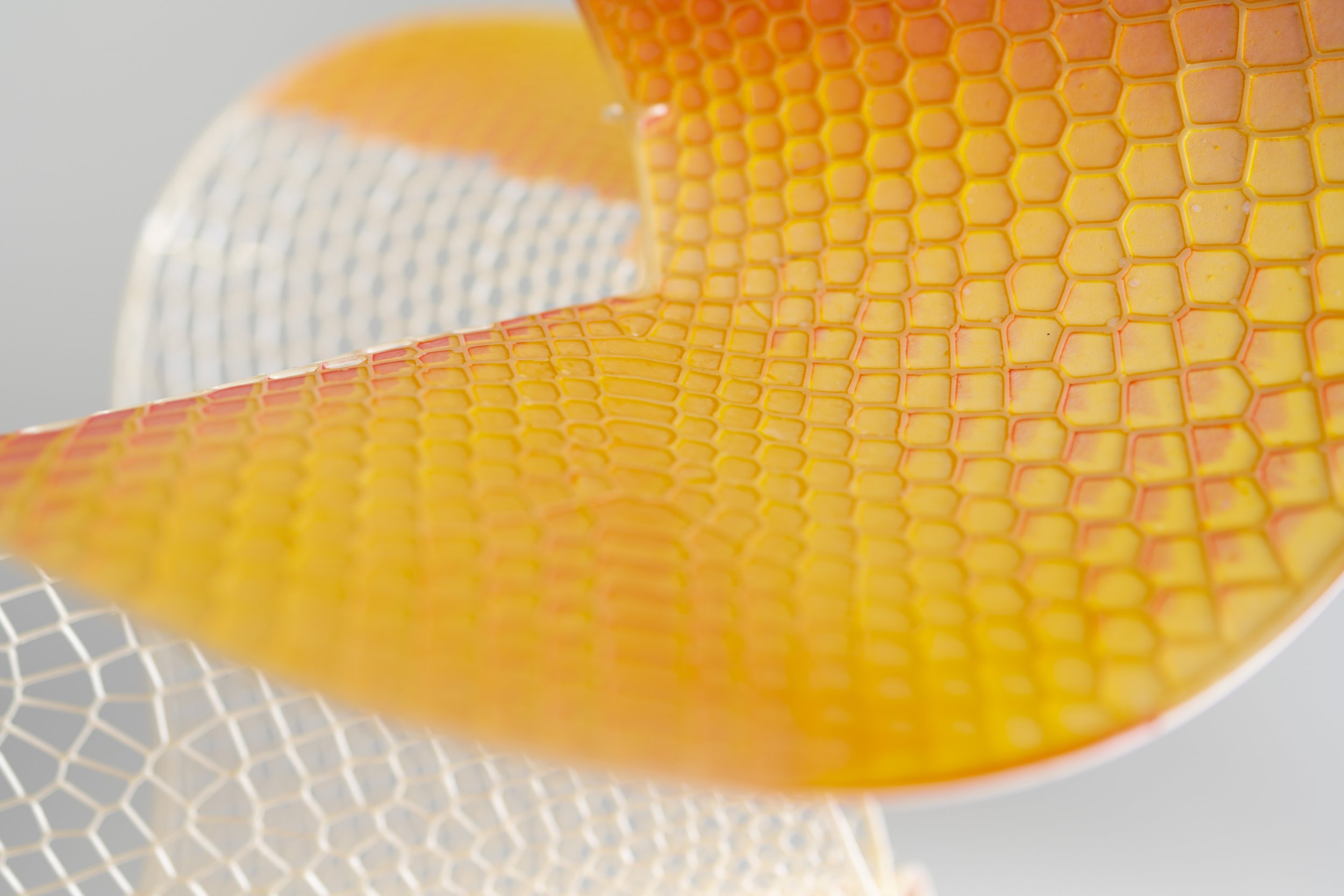

Sensbiom 2 by Crafting Plastics! & DumoLab

Images by Crafting Plastics! Studio

Crafting Plastics is a Bratislava-Berlin based studio design research studio, set up by Vlasta Kubušová and Miroslav Král, with the aim of integrating responsive biomaterials into our everyday lives at scale. Their Sensbiom 2 project is created in collaboration with DumoLab, a research lab with a shared ethos based in the University of Pennsylvania Witzman School of Design. Sensbiom 2 is the perfect example of their intentions in motion – swirling laser-cut biopolymer lattices, with pastel hues that shift to signal real-time changes in solar radiation, making those present in the room aware of the invisible elements within our environment.

“The decision to emphasise beauty over creating a visually intimidating piece was quite intentional,” Kubušová smiles. She describes viewers' reactions as ranging from surprise to shock, leading to some profound and insightful conversations. “Our goal was not to alarm, but to encourage contemplation. The project successfully made the invisible tangible — since our perception of the world is largely visual, we hope that this approach enhanced understanding and sensitised thoughts about the climate's impact on living beings.”

“The lattices are 3D printed with Nuatan, a 100% biodegradable and biobased bioplastic developed in our studio,” Kubušová explains. “They are cast with an interactive cellulose-algae-based biocomposite skin with photochromic components that react to UV radiation exposure. To maximise the environmental interaction, we decided on three-dimensional forms, a geometric design inspired by the complex patterns of the mineral outer skeletons typical of certain radiolarian organisms.”

Kubušová is passionate about the power of biomaterials to help us better connect with nature. “We exist in a world of materials and are ourselves composed of matter. However, the lifestyle of our era often leads us to overlook and neglect the materials around us. Many materials, especially oil-based plastics, have made us insensitive. They simply serve us without providing any information or connection. In contrast, augmented biomaterials present an opportunity to deepen our understanding of environmental changes. They can act as mediators or lenses, enabling us to see, feel, smell and experience our surroundings in enhanced ways. Developing new materials with dynamic, life-like qualities could become a vital tool in addressing the climate change crisis.”

“We shouldn't view the introduction of new materials as a solution to all our problems,” Kubušová caveats, pragmatically. “Instead, we should aim for diversification, testing multiple iterations on a small scale initially. A common argument against new materials is their inability to match the durability and properties of commonly used, inexpensive, non-biobased materials. However, I believe that the more we explore alternatives and persist in our efforts, the more effective and affordable these materials will become, hopefully replacing a substantial amount of oil-based and toxic materials. In an ideal world, we would have access to an abundant supply of locally sourced and produced materials for various applications, keeping non-biodegradable materials for areas where they are truly necessary.”

“We shouldn't view the introduction of new materials as a solution to all our problems. However, the more we explore alternatives and persist in our efforts, the more effective and affordable these materials will become“

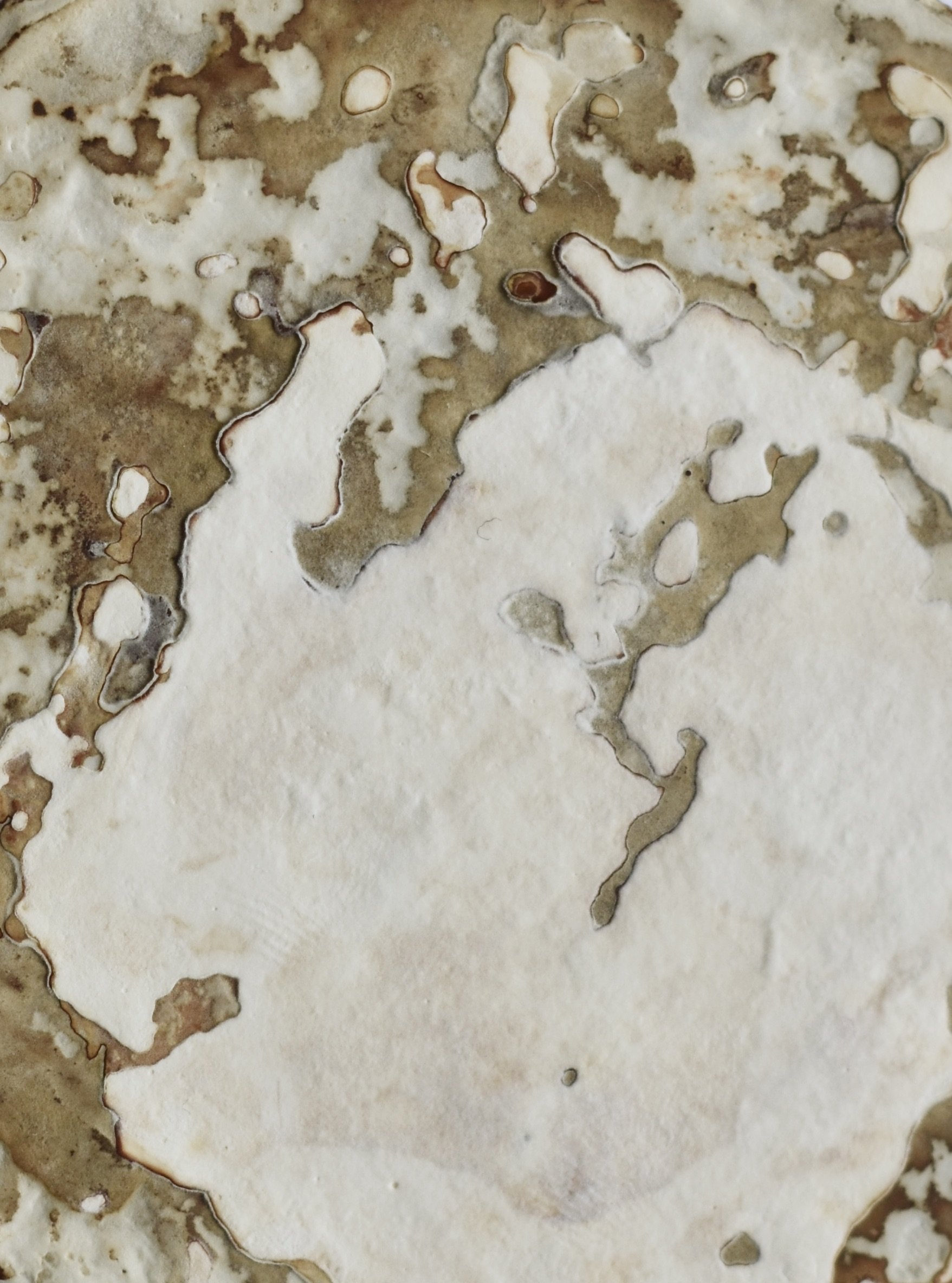

Tea & Biscuits by Simon Frend, Dyingarts

Images by Simon Frend

Dyingarts is a new Bournemouth-based studio founded by artist Simon Frend, dedicated to making cremation urns with circularity at their centre. The concept evolved over decades of coffee chats, coastal walks and artistic experiments — including an exploding canopic vessel containing animal organs, a repurposed nappy cream tub containing his Dad’s ashes, and the desire to work with materials that give something back to the environment. “These ideas have been fermenting over time,” Frend tells Looms. “Experimentation is absolutely the heart and soul of it all.”

“There are various starting points,” he continues. “There’s place, there’s ritual, there’s material. There’s a lot of walking involved, collecting and handling the materials — that’s a time when you can be quite reflective and creative. Hopefully, people will find their own way into the work, there will be a resonance, a memory… Sometimes the concept comes to mind before I get my hands on the materials, for example with Tea & Biscuits and Americano & Newspaper.”

His Tea & Biscuits urn required a serious commitment to tea-drinking from Frend, as well as a good amount of patience. “It’s a surprisingly difficult material to work with, because it wants to go mouldy and biodegrade all on its own, so you have to get it dry as quickly as possible. The other difficulty is that it shrinks a remarkable amount. You need quite a lot to start with, but it’s also about controlling the shrinking so you can get pieces that will fit together. Getting the recipe right, the thickness, the drying period, that all takes a bit of time. But, I think I’ve cracked it.” The organic matter of the urn is intended to add back to the fertility of the soil, counterbalancing the nitrogen contained in ashes in a positive and gentle way.

Frend also makes urns for water send-offs. “I like the idea of going back into the sea, there’s something quite poetic about it. I’ve always lived on the coast and I can’t imagine living away from the edge,” he says. “These urns are designed to dissolve as quickly as possible, between tides. As soon as they hit the water they start to dissolve, they’re not dependent on heat or microbes or anything else. If there’s a bit of turbulence, that will help too.” A long-time mudlarker, Frend also found treasure down on the shores of the Thames while at London Design Festival’s Material Matters. “I spent some time on the beach below OXO tower at what is known as 'Old Bargehouse Steps' (which has a fascinating history) and collected washed red brick, chalk and coal, which I intend to work with to make a site specific vessel.”

Dyingarts is a collective, featuring the work of others — including urns carved from felled trees by master-craftsman Paul Reeves — sharing a mutual sense of symbolism, ritual and respect. “It was always designed to be more of a collective or a gallery,” Frend notes. “That context is really critical for me. I don’t want to be competing with or compared to companies selling products that are mass-manufactured. We occupy this small niche – essentially art, with craft and design in that mix, but intending to sell to a knowing market, those interested in something that is a bit more unique and meaningful to them and to the planet.”

“There are various starting points. There’s place, there’s ritual, there’s material. Hopefully, people will find their own way into the work, there will be a resonance, a memory…”

Fumo Panels by Malina Tezycka, MyLab

Images by MyLab

Polish architect Malina Tezycka had little experience in biotech when she was first drawn to mycelium, but her overriding passion for natural materials motivated her to experiment. “I was interested in mycelium because of its unique properties and incredible potential for a sustainable future. For me, it wasn’t just about creating a product, but about the entire process, and the concept of biofabrication, which is unlike anything in the world of traditional manufacturing. It’s harmonious between nature and humans, where the materials essentially grow themself with minimal intervention,” she tells Looms.

Studying for her Masters in Architecture in Sweden, mycelium became the obsession that formed the basis for her thesis and led to her founding MyLab and creating Fumo Panels — bio-fabricated wall covering panels entirely consisting of fungal mycelium and agricultural waste like hemp and sawdust. It’s a next-gen material that’s 100% biodegradable and compostable, with an almost zero carbon footprint. The wall panels also happen to be beautiful, creating modular works of art and naturally sound-proofing interior walls. “It’s very unique, no two look exactly the same,” says Tezycka.

Currently, she’s using a mycelium substrate sourced from The Netherlands, but she’s working on growing her own and experimenting further with its application. “Architecture provides this great canvas for harnessing mycelium’s sustainable and customisable properties — it could be used in various ways. It’s a really interesting field; plus, there are a lot of materials we haven't even discovered yet, infinite potential. Mycelium has been underneath us for billions of years, but we only discovered it could be used as a building material about 20 years ago.”

Commenting on the perceived impact of new ‘sustainable’ and ‘eco’ materials, Tezycka is hopeful. “Our overall goal should be continuous improvement and striving for better alternatives that reduce environmental impact,” she says. “I have a quote by JK Rowling at the very beginning of my Masters thesis: ‘The world is full of wonderful things you haven't seen yet. Don’t give up on the chance of seeing them.’ I think that summarises everything.”

“Architecture provides this great canvas for harnessing mycelium’s sustainable and customisable properties…

Plus, there are a lot of materials we haven’t even discovered yet, infinite potential”