The Mycelium Revolution

Meet the man persuading industry giants that mushrooms can change the status quo

Words by Farah Shafiq. Images by SQIM/Ephea/Mogu

The potential of fungi is much discussed in the design world, with many pioneering solutions. Over the last two decades we’ve seen an increasing trend in new patents for fungi to be used in functional materials, an uptake that’s forecast to continue well into the future. Today, these biomaterials can be found in the worlds of packaging, fashion, architecture and beyond (even as a solution to demolish abandoned houses), where advantages compared to synthetic materials are applauded, including low cost, safety, biodegradability and relatively low environmental effects. Media, too, are very much on the mycelium bandwagon. It’s far from an unexplored or underreported subject.

So, what makes Maurizio Montalti’s work stand out? As Chief Mycelium Officer at SQIM he is on a mission to get the biggest mass-market players on board — and so far, he’s been extremely successful. At the beginning of 2024, SQIM closed an €11 million funding round. Key investors included CDP Venture Capital, ECBF VC, Kering Ventures and Progress Tech Transfer, consequently powering up the activities of SQIM and of its two main brands — ephea™️, which is focused on biofabrication of flexible materials for the fashion industry; and mogu™️, which creates innovative interior and building products, such as flooring systems and acoustic/decorative panels.

This investment will enable SQIM to intensify its research and experimentation, to design, evolve and scale mycelium-based technologies and deliver these at industrial level, mastering both the micro and the macro. It's the macro that seems to be the biggest challenge for most in this area, so we were interested to get Montalti’s take on how SQIM is approaching this upscale. “The funds will accelerate our growth further and faster, while significantly boosting R&D efforts too,” he shares, enthusiastically. “We’re already expanding our team, widening the scope of competences and functions, and improving current production lines. In parallel, we are creating a demo production facility. Overall, this will allow for the most effective penetration of our materials and products in fashion, interior, automotive, and many more markets.

It will demonstrate that shaping a more ethically and ecologically responsible industry is not a farfetched dream at all.”

“I often describe it as a positive spiralling vortex – as soon as you dive into the fungal world, you’re captivated, and the more you fall, the more the fascination expands and the opportunities grow. It’s incredible…”

Maurizio Montalti, Chief Mycelium Officer at Sqim

(Pictured above, from left to right) The key people behind SQIM: Maurizio Montalti, Serena Camere (Industrial Designer), and Stefano Babbini (CEO)

“Since we founded the company in 2015, things have changed dramatically,” Montalti tells Looms, speaking from SQIM HQ in Varese, northern Italy. “We work in a business ecosystem where available financial resources for innovative companies tend to be less abundant than elsewhere, say Silicon Valley for comparison. This can be considered a positive though, as it really pushes us to get the most out of what we have available.” In the case of SQIM, this consists of raw feedstocks, namely low-value, residual biomasses from agro-industrial and manufacturing processes, including different types of straw, hemp shives, pre-consumer-waste cotton fibres, spent coffee grounds, discarded seaweed, and oyster and clam shells (another alternative material that’s taking off). Advanced bio-technologies, together with extended data collection and analyses, then help pave the way to SQIM’s products, their influence and ambition.

Given the opportunity, Montalti is more than happy to extoll the mystical and magical wonders of the mycelium kingdom. But, he’s well aware that the performance-based argument is most effective when convincing the mass-market. He is conscious, always, of the words he chooses and his role within the wider narrative, keen to swerve the obvious avenues that speak to “harnessing the potential of nature”, or promise to create “zero impact”. Interrogating the language we use, the way we think about, and our motivation for creating these “sustainable” solutions (another word he’s not such a fan of) is key for the Italian designer and inventor.

Ephea™️, one of SQIM’s two main brands, creates versatile materials for fashion (Brown Suede pictured here) based on 100% mycelium as the sole ingredient

Who’s Really In Charge?

SQIM evolved along with Montalti’s passion for mycelium. “I often describe it as a positive spiralling vortex – as soon as you dive into the fungal world, you’re captivated, and the more you fall, the more the fascination expands and the opportunities grow. It’s incredible… Fungi are the great decomposers, at the heart of transformation. They are the ultimate alchemists and regenerative agents in the ecosystem, allowing for a continuous flow that goes beyond the very basic idea of circularity. ”

Though many who work in this field consider themselves ‘collaborators’ with mycelium, ever analytical and precise, Montalti questions this idea. “We are very presumptuous when we describe collaboration with other non-human living systems. Back in the day I used to think of it as a ballet: we are the choreographers, here to guide the dancers who are the stars of the show. But, how presumptuous is that? To assume I’m in charge, when those creatures have been leading the way for much longer.”

With that in mind, Montalti cultivates a way of working that is carefully attuned. “I started this investigation many years ago, as a designer in a white coat, approaching biological processes through the lens of the non-expert, with the creative freedom to challenge the usual teachings, which has proven to be of great advantage for manifesting ingenious intuitions,” he says. “The way science works is typically rooted in observation; yet, I believe that it is important to also consider an empathetic relationship with mycelium, understanding mutual needs as living processes unravel before our eyes. That capacity to not just carry out a series of steps, but to really connect is something I now try to pass on to my team.”

The specifics of these steps are fascinating nevertheless. It all starts with thorough research to identify the fungal strain and a suitable nutritious feedstock composition (which could include a blend of several biomasses). The feedstock is first hydrated, distributed in special bags, and then thoroughly sanitised/sterilised, by cooking at high temperature. After cooling, it is inoculated with the selected fungal strain, and the bags are sealed and transferred to a growing room at fixed temperature. At this point, the mycelium starts colonising, transforming and assembling the nutrients into a unified mass. Many different parameters, including temperature, humidity, pH, gas exchange, etc. can be varied to obtain raw mycelium materials with different qualities and specs.

After several weeks, once the mycelium colonisation process has reached the desired stage, the incubated feedstock, containing both mycelium and plant biomasses, is ground down to particle size or brought to a semi-liquid state, depending on the objective. This mixture is distributed in static bio-reactors or dedicated moulds, where the mycelium grows back very quickly, taking the shape of its container, while structuring its micro-filamentous cells in and around the residual feedstock’s fibres (in the case of mogu™️’s mycelium composite materials), or growing on the surface of the feedstock (in the case of ephea™️’s 100% mycelium materials). Once the growth is complete, the harvested raw materials undergo a drying treatment at a low temperature to stop the growing process, and then measured one by one and their quality checked. The post-processing step depends on the final application, to turn the bio-engineered raw materials into effective marketable products.

Forging A Unique Standard

Of course, with significant investment and funding, comes challenge – how to scale up and standardise products and processes whose selling point is their uniqueness? “The ubiquitous nature of the market is what we’re trying to change in the longer term, but also what we need to comply with today in order to be able to succeed in this goal,” Montalti notes. “So, it’s a bit of a duality, with a clear long-term vision, but inevitable short-term needs too.”

The way forward is, he suggests, turning perfectionism on its head. “I personally believe that imperfection isn’t valued as much as it should be – that’s one of my ultimate goals as a creative. One of the most amazing things about these materials is their uniqueness, and the consequent possibility to create truly unique final products, that speak the language of the processes from which they derive. This is exactly what we are missing in the objects and products we surround ourselves with, from our interiors to what we wear. Appreciating how any material is capable of communicating about its origin. Despite our good achievements towards standardisation, I truly hope that this vision of recognising imperfection and partial unpredictability as positives will increasingly manifest.”

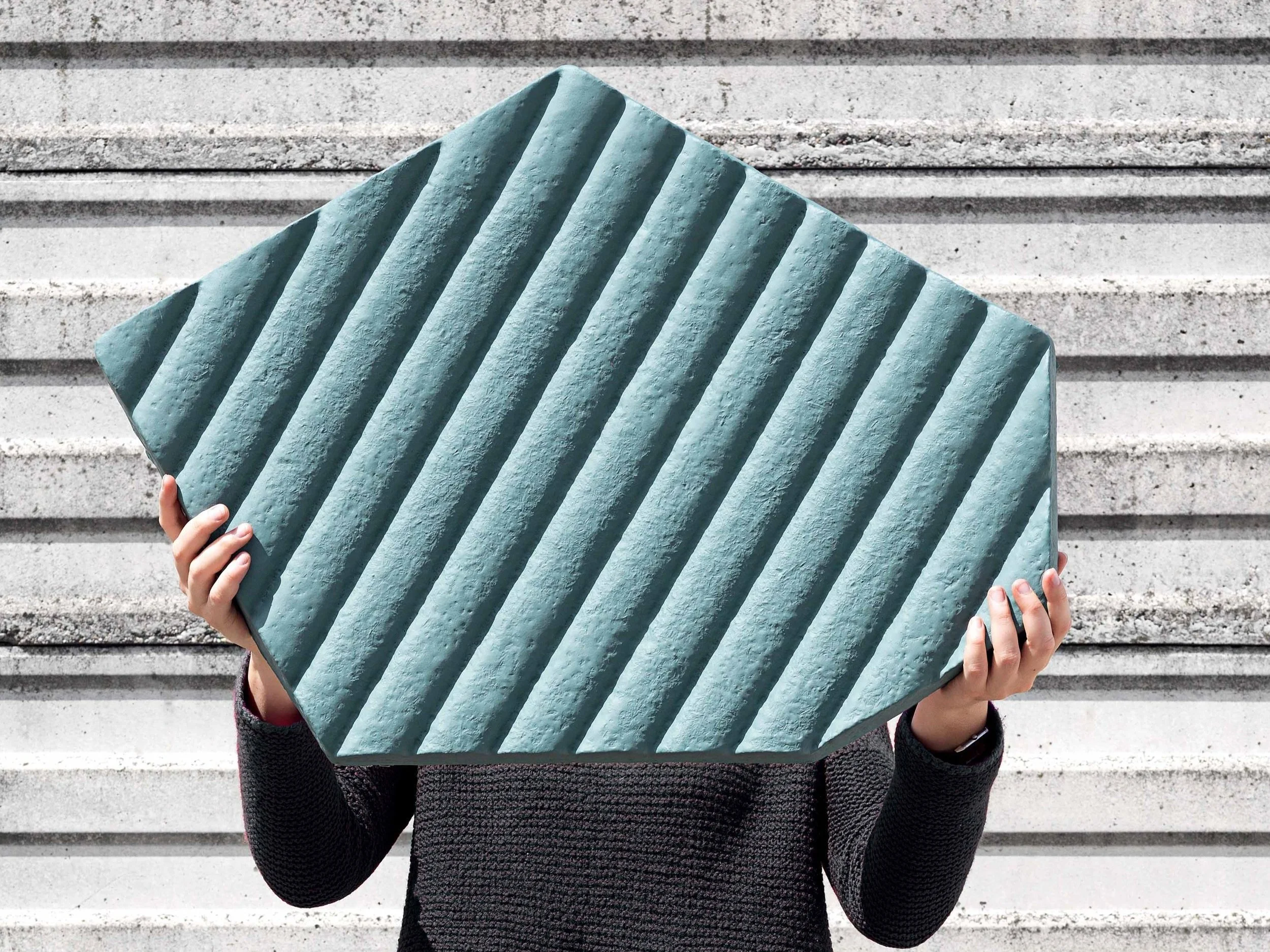

Restaurant interior finished with mycelium-based floor tiles and decorative wall panels by mogu™️

Working Towards The Holy Grail

“When it comes to fungi, in terms of application, the sky’s the limit – in fact, you can go beyond,” Montalti confirms. “It’s such an unexplored and pioneering world. Currently, we are attempting to create a revolution in material culture and innovation; one that’s rooted in biology, creating materials that perform and that at the same time resonate with the lifecycle of the larger ecosystem, requiring the least amount of resources to be produced, being long-lasting but degradable – in short, that’s the holy grail. But it will take time to fully reach this objective, it’s not possible to have it all immediately. It’s a process rooted in constant incremental progress, requiring major efforts in a field that is just starting to take off.”

“Currently, we are attempting to create a revolution in material culture and innovation;

one that’s rooted in biology, creating materials that perform and that at the same time resonate with the lifecycle of the larger ecosystem”

With the potential of mycelium as vast as it is, it’s an area of exploration that’s ripe for exaggeration. “The media tend to present sensationalised narratives that often lack evidence or are anticipating something that’s not yet concrete. Media are largely filled with ‘fake it till you make it’ stories that feed organisations with attention. As such, we’re trying to respond in a completely different way. For us, it’s important to practise honesty and transparency, being clear about the status of our technology, what is fact and what is vision. ”

Ten years, he says, will be a relatively short time-frame in the grand scheme of things. Yet, “I hope in 10 years’ time to see quantifiable impact, or a fraction of impact – I’m not talking about zero impact, because I don’t trust in that type of narrative, nothing has zero impact, everything uses and emits energy, it’s about how to neutralise potential impacts and compensate accordingly. Or even better, it’s about striving to work as a fungus would: with nature, for nature and as nature. I certainly hope that in a decade these materials will have started massively penetrating the market, and I feel pretty confident that we will get there.”

Follow @mogumycelium & @ephea_mycelium to stay up to date with the mycelium revolution.