Nature Is Our Most Powerful Tech

Photographer Luca Locatelli presents a world of nature-based future solutions

Words by Emily McDermott

‘Nemo’s Garden’ in Noli, Italy, 2021; image by Luca Locatelli

From ultra-farming in the Netherlands to Dubai’s ‘sustainable city’ housing development, Locatelli has been documenting what he calls “future solutions” for nearly 15 years, with his photographs and projects published in international media outlets including National Geographic, the New York Times and the Guardian. However, in the past three years, the renowned photographer has refined his focus to explore initiatives related specifically to the development of the circular economy. He travelled to 18 different sites across Europe to document some of the most groundbreaking initiatives, and the resulting photographs, videos and sound installations formed the basis of his exhibition titled ‘The Circle’ at the Gallerie d’Italia in Turin.

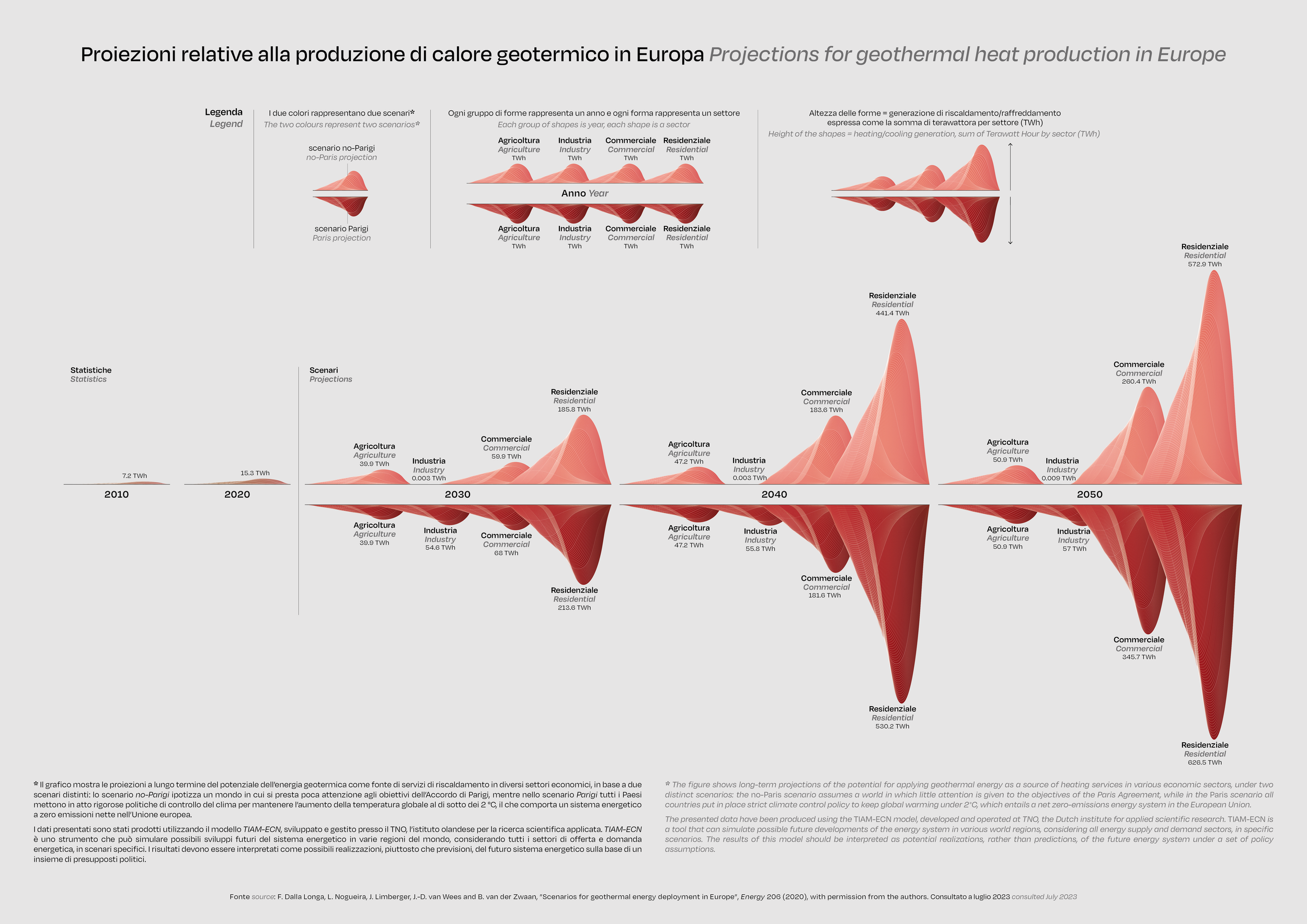

Locatelli’s visual documentation stands out for its abstract beauty. Though his work is indeed a form of photojournalism, he shows subjects from unconventional points of view. Paired with informative wall texts, stunning data visualisations by Federica Fragapane, and knowledge support from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, ‘The Circle’ presents nature-based solutions, reframing nature as a type of technology, so the audience is able to better understand its potential.

“My work revolves around the making of the future, particularly with a focus on solutions for the climate crisis”— Luca Locatelli

Images by Luca Locatelli

Recently, Locatelli spoke with Looms about how he first became interested in circularity, the innovative underwater biospheres he encountered along the way, and how the key to saving nature lies in the ability of nature itself.

What initially drew you to the topic of sustainable solutions for the future?

I started my career as a photographer and environmentalist in the Amazon, as a founder of the NGO Amazonia. We work with local people to protect 600,000 hectares of intact forest. At the beginning, I used photography to spread the voices of local people in the Western world; to share the importance of conservation and keeping the Amazon intact. As I developed my career, I wanted to investigate what we were really doing to contribute — there wasn’t so much happening back then, around 2008, but I was determined. As the climate crisis became increasingly evident to more people, international media gave me funding to continue my investigation. Since then, the media attention has grown and I’ve never stopped.

Can you tell me about one of the first projects you encountered?

It was in Singapore in 2010. At that time, Singapore was building its reputation and the visionary statesman Lee Kuan Yew believed greenery was important to attracting investors and creating a better condition of life; he believed in making Singapore a “garden city.” I was attracted by his pragmatic but clean vision of a city-state, especially when surrounded by many cities that are so polluted you cannot even breathe. In Singapore, you can breathe, and the temperature is cooler.

The exhibition in Turin was the world premiere of Locatelli’s photographs from his two-year research journey across Europe. Images by Andrea Capello

How did your project ‘The Circle’, which is specifically focused on initiatives related to the circular economy, come about?

After almost 10 years of always being on assignment, Covid hit and I had the chance to revisit my archive. I edited down everything I’d ever done and connected dots that have been evident throughout my practice, realising that the most attractive pictures were those that did not compromise my artistic vision. However, these photos only accounted for about 30% of my archive the other 70% were aimed at being published. I decided I wanted to do something important with my work, which led me to develop the concept of ‘The Circle’. When the pitch got the green light in 2020 I felt like I could really do this!

How did you decide when to incorporate moving images and sound?

Sometimes I felt like photography was the most powerful. Sometimes it was video. Sometimes just audio. For example, there’s this incredible industry of mussel farming in Ría de Arous, Spain, with 2 million cords going 30-metres deep underwater. When you dive there, you’re inside a forest of these cords, and I immediately knew it would be incredible to make a video. At the same time, I thought the biodiversity created by the mussels was an incredible opportunity for photography.

Within the ‘Circle’ exhibition, data visualisations by Federica Fragapane enter into dialogue with the themes addressed by Locatelli: showing the potential geothermal heat production in Europe, historical trends in energy from renewable sources, and more.

What’s one of the most surprising initiatives you came across when developing ‘The Circle’?

The biosphere project Nemo’s Garden, which is a pioneering vision of underwater farming. It combines the power of photosynthesis with the power of the ocean. The ocean is the biggest tank of CO2 in the world, which the plants need to grow, along with the sun’s reflection in the water, which amplifies the light and enables photosynthesis. Then there’s the technology of the biosphere itself, which creates the necessary humidity. It looks very futuristic, but it’s very simple. And although it was designed for places like Dubai, where there are harsher conditions for traditional agriculture, the ocean could be a solution to create food elsewhere in the world, too. If we can use nature and create a beneficial relationship for both sides, we can solve a lot of problems.

Luca Locatelli at the launch of ‘The Circle’. Image by Andrea Capello

Finding nature-based solutions was one of the key focus areas of ‘The Circle’, right?

Yes, it’s about finding solutions for environmental and social issues with natural features. It’s nature saving nature. With ‘The Circle’, I explored industrial symbiosis, growth-field regeneration and nature-based solutions, but nature-based solutions magnetised me the most. They’ll be the focus of my next project. I’m eager to continue this path of investigation, because nature is the best device we have for creating solutions for the climate crisis. Even with technology, we aren’t able to create a machine as wonderful as nature.

It’s interesting to think about nature as a technology...

Exactly. We have reached the point where if we connect nature to devices, it becomes more comprehensible. It’s absurd, but it’s true. And that is my visual intention as well, to photograph nature as a device.

What do you think photography and video bring to the conversation that statistics or words alone don’t convey?

Photography and videography are a trick to drag you inside the information. With my work, you know you are seeing an exhibition about solutions for the future and that you are at an exhibition of a documentary photographer. So, you know the photos or videos are real and not generated. But at the same time, the images are not comprehensible at first glance; you don’t necessarily understand what you’re seeing. That is the trick I’m using to attract people to the information. Words are the most powerful tool we have to communicate with each other, but sometimes it’s difficult to communicate science or scientific data; it’s there but no one is reading it because it’s not comprehensible. So, the visual side of journalism and science can be used to bring people into the information. Photography can open the emotional level to allow information in.

Lac des Toiles, Switzerland — the world's first high-altitude floating solar park where 2240 sqm of solar panels cover 2% of the surface area of an artificial lake, against adverse site conditions. Image by Luca Locatelli