AI Art Imagines New Species

Entangled Others, aka artists Sofia Crespo and Feileacan Kirkbride McCormick, conjure new species to help us better understand the natural world

Words by Emily McDermott

‘Critically Extant’ on Times Square; images by Michael Hull, courtesy of Times Square Arts

Combining deep learning with scientific research on the natural world, artists Sofia Crespo and Feileacan Kirkbride McCormick make the intangible tangible. Under the collective name Entangled Others, the Lisbon-based duo aims to help foster emotional ties — and, in turn, promote conservation — to our often-invisible connections with other lifeforms. Using artificial intelligence to help visualise such complex entanglements, the pair frequently creates digital 2D and 3D images, which live online as NFTs, JPEGs and immersive websites, as well as in the physical world as photographs, moving-image installations and embroidered tapestries.

‘Artificial Remnants’ images by Entangled Others Studio and XuBo

The two artists met by chance when McCormick came across Crespo’s ‘Artificial Remnants’, a series of generated speculative, artificial insectile life based on data of existing species. “The intention is to celebrate the natural diversity of insectile life, not through the precise, sterile digital reproduction of it,” Crespo writes, “but in the form of new specimens that are digital natives.” By seeing imaginative, beautifully rendered insects in a space like the digital world — a place we’re more familiar with than, say, the depths of a jungle — our human perspective toward such species can be changed: they are no longer invisible, no longer an ‘other’.

When McCormick, fascinated by this series, retweeted the project, Crespo looked into his practice, which also resonated immediately. So, she reached out to see if he’d be interested in helping translate her two-dimensional ‘Artificial Remnants’ images into 3D. “At the time, there wasn’t a very mature generative 3D, or AI for 3D,” McCormick explains. “So, we joined forces and spent a while figuring out ways to coax two-dimensional neural networks to produce 3D outputs.”

The rest fell naturally into place. During our conversation, we spoke about artistic licence when dealing with data, nurturing emotional connections to the natural world through technology, and an upcoming research expedition to the Amazon rainforest.

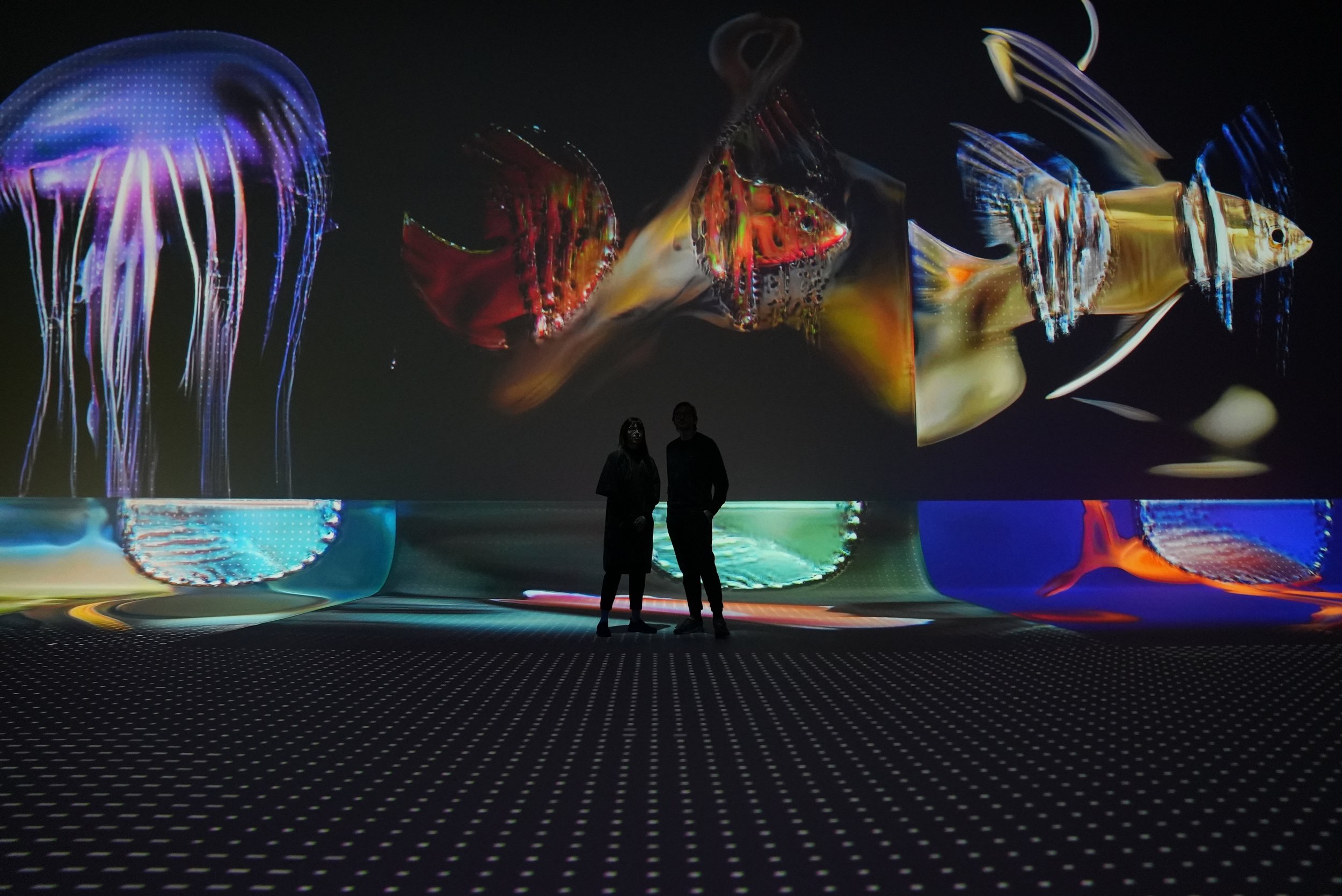

‘Decohering Delineation’, images by Sam McCormick, courtesy of NXT Museum

At what point did you decide your collaboration needed a name and presence of its own?

Sofia Crespo: Around 2020, with the pandemic, all our projects were cancelled. We knew if there was going to be a time where we would have time to rethink what we were doing, this would be it. So, we wrote a lot of words on a board next to our monitors and those that resonated the most were ‘entanglement’ and ‘the other’. ‘Entanglement’ builds connections — it’s about being connected to or existing in relationship to — whereas ‘the other’ builds separation, it creates ‘me’, ‘this’, and ‘them’. There is an almost contradictory synergy between these words.

Feileacan Kirkbride McCormick: At the same time, there’s the underlying fact that we can never know what it’s like to be a fish, tree or bird, yet we cannot exist without them. They are forever part of our world and the interactions we have. We are inescapably intertwined with the ecosystems around us, whether we see it or not.

Image by XuBo

Sofia, you’re an avid diver and have previously researched jellyfish — what first drew you to ecology?

SC: It was a topic that magnetised me over time; but also, as soon as I became more interested in computers, I wanted to use them to understand the biological world. I was interested in the idea of technology — that which is artificial and human-made — connecting us with things that have existed for millions of years. I researched and rendered jellyfish, and I also got into the habit of collecting tiny samples [from the natural world] and looking at them under a microscope. It was amazing to see these tiny cells and structures, these intricate things that were happening and can’t be seen by the naked eye. This awakened endless curiosity.

At what point did AI enter the picture?

SC: In 2017, I was working on a project called ‘Trauma Doll’, which was related to net art and the future of photography. I started to think about what patterns would emerge if an AI could look at my browser history: would an AI be able to identify trauma? Could an AI learn trauma like humans do? It was a way of understanding myself and how I was spending my time on the internet. Eventually, the draw towards the natural world was stronger, because it connected me to something that was much bigger than myself.

Image by Entangled Others Studio

Feileacan, where did the nature-tech-art connection arise for you?

FKM: I grew up mostly in Norway, always in and around nature. When I was seven or eight, I saw a TV report about global warming and my young brain latched onto that as something relevant and important. I was also fascinated by land art. I eventually decided I wanted to record and use natural, three-dimensional shapes but in non-destructive manners — I thought I could bring nature to people in the digital space; I could capture a whole tree without having touched it once. Also, it doesn’t scale very well to drag people into the woods. [Laughs.]

How would you define the work of Entangled Others?

SC: The concept of entanglement is so abstract and invisible that it’s hard to grasp and make tangible. Humans are not fully equipped to understand the complexity and intricacy of these networks of connections. So, our projects aim to make tangible the sense of wonder toward the natural world as well as the idea of existing in relationship to something else.

FKM: We’ve especially been trying to find ways of nurturing emotional connections to aquatic life, which is famously hard for humans to connect to on an emotional level because there is a body-form overlap.

How do you go about selecting the ‘others’?

FKM: We try to look at species or ecosystems that could use the extra focus. Animals you typically think of when you hear “endangered animals,” like larger mammals, receive a lot of attention — there’s so much more we need to talk about, too. So, a lot of our work has been around the aquatic, because marine life and the importance of it — for the air we breathe, the food we eat, and biodiversity in general — is still vastly underrepresented.

Image by Michael Hull, courtesy of Times Square Arts

Tell us about the ‘Critically Extant’ (2022) series, which recreated some of these underrepresented endangered species.

FKM: For that project, we used the biggest openly available, commercially licensed dataset to create a cutting-edge transformer model that recreated different species. We asked ourselves: “What would we know about these species, 40 or 50 years from now, with the data we currently have if they were to go extinct?” Because this technology is so hyped and we have the feeling we know everything these days, we wanted to question whether we could actually reconstruct these species? The reality is no. Not at all. So many of these species don’t even have an image to them — we were making that tangible.

Do you ever build your own datasets?

SC: It depends on the project. In ‘Critically Extant’, we used an open-source dataset, because the whole point was to look at how creatures are represented. But for other projects, we build our own. The most challenging are 3D because there’s very little 3D data available to work with. For example, 3D meshes of marine creatures are hard to get, and a coral reef ecosystem is very difficult to scan underwater. So, sometimes we find ourselves in the position of creating artificial data.

FKM: For example, for the corals in ‘Beneath the Neural Waves’ (2020–22), we collaborated with an artist who, based upon scientific papers and research in the wild, built a series of generative algorithms that grew coral in 3D. Because we’re artists, we don’t have issues with creating our own data. As long as it serves our concepts, we give ourselves a little bit of licence.

Image by XuBo

Can you share a preview of your next project in the Amazon rainforest?

FKM: We’re working with two researchers from Projeto Mantis, which examines praying mantises in the Brazilian rainforest and raises awareness about them. As artists, we have the same goals to help encourage conservation, so together we applied for and received a grant from National Geographic for a month-long expedition. We’ll work with the scientists to collect data about praying mantises, and then the outputs will go in two different directions: they’ll release scientific research, and we’ll work with the data to create artworks.

SC: One of the goals of this project is to assess what species of praying mantises live in the rainforest, but specifically not in the reserve we’re visiting. We will photograph the species we see and then digitally segment the praying mantises’ body parts and use generative tools to create variations on these shapes and imagine what other species might exist.

Looking back on your journeys as artists thus far, what is one of the biggest things each of you has learned?

SC: I've had a life-long fascination with the microscope, not only because it revealed all the amazing life around me but also because it is a technology that has brought us closer to nature. In my practice, one of my biggest learnings has been the process of using technology as a paintbrush to share the inspiration and amazement I feel about the natural world.

FKM: What has been a personally important process for me is that of learning, developing, and nurturing the tools that allow not only for an interaction with the more-than-human through a persistent practice, but an ever deeper, richer appreciation of the incredible biodiversity and value of the world we are but a small part of.

Image by XuBo