Artists For The Oceans

Discover three artists who reflect on the importance of Earth’s bodies of water, and the damage they endure

Words by Emily McDermott

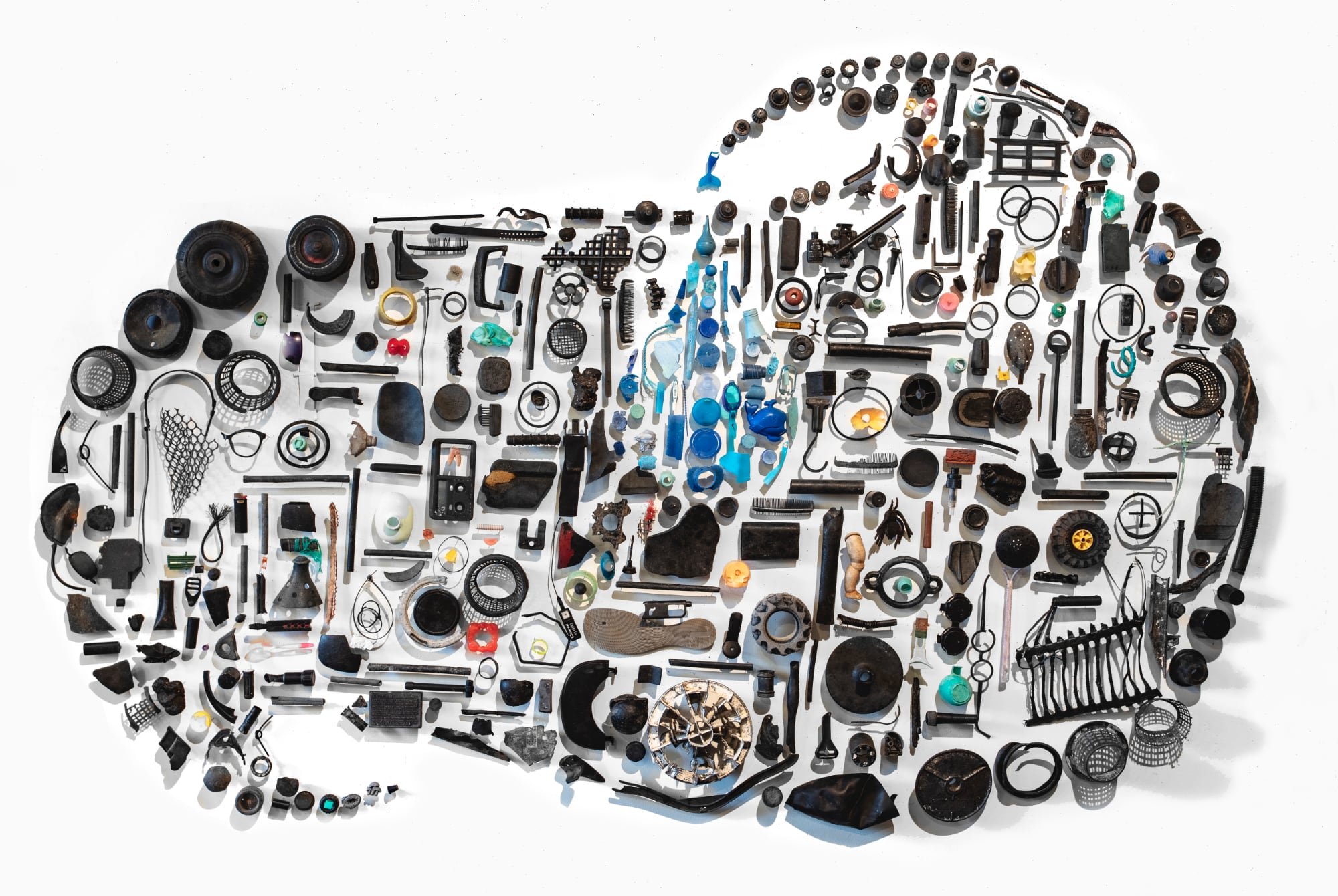

‘Ocean Archaeology of Our Time’ (2023) by Pamela Longobardi; image courtesy of Patina Maldives

Whether working in film, sculpture, painting or installation, artists can often help us to see the world from new perspectives, reframing issues and presenting gateways to potential solutions. Recently, those that have captured our attention are the creatives honing in on the oceans and seas that cover 70% of the Earth’s surface; vast bodies of water that feed us, regulate our climate, generate the majority of our oxygen, act as a conduit for economy and industry, and provide a home to an estimated 2.2 million species.

Pamela Longobardi, Tim Georgeson and Courtney Mattison are just three artists visualising these connections to the oceans. Their work traces how bodies of water connect global societies and cultures, how they carry the stories of the past and the present, and how they are living evidence of human impact on the planet. “We’re treating the ocean like our toilet,” Longobardi tells Looms, not holding back in conveying her outrage at the near 8 million tonnes of plastic that ends up in the water every year.

Her work, like that of Georgeson and Mattison, is designed to encourage us to rethink how we treat the planet’s vital ecosystems, and how we can all prioritise their protection and regeneration. “It isn’t just one place’s plastic. It’s everywhere. We’re all involved in it, and the ocean is moving it as a giant engine. Plastic is at the centre of climate change. It’s in bed with oil and these petrochemical lobbies that are so powerful. It’s all connected.” And this isn’t just about humans: it’s about every connected lifeform on land, under the sea and in the sky. Here, we speak to all three artists, drawing motivation and inspiration from their oceanic renaissance.

Pamela Longobardi: Plastic Messages from the Ocean

‘Swerve’ (2019) and other iconic artworks from The Drifters Project by Pamela Longobardi

When Longobardi was on the Island of Hawai‘i, otherwise known as The Big Island, in 2005, she witnessed firsthand an inconceivable amount of plastic and other waste piled up on a black-sand shoreline. “It smacked me like a tonne of bricks, to see these mountains of coloured plastic materials that were being vomited out of the ocean,” she remembers. She went back to the beach a few days later with a duffle bag, filled it with discarded materials, and took it home with her. From the rubbish, she created two treasures: Driftweb, a spiderweb-like installation made from fishing nets tied together, and Defective Flow Chart, a sculptural piece installed on the floor made from plastics. The following year, she founded the collaborative artistic research initiative Drifters Project, which investigates ocean plastic through art, activism and social change, including beach clean ups around the world.

“I take people through a ‘forensic beach cleaning training’: we have to not think of ourselves as janitors but as detectives,” she explains. “I really believe the ocean is a conscious entity, and it is, in some way, using this plastic to communicate its ill health with us. The plastic is a message from the ocean, and we’re looking for clues.”

Supported by the Patina hotel team, Pamela spent 10 days collecting plastics around the Fari Islands, which she sorted and transformed into a 1,000-piece artwork titled ‘Ocean Archaeology of Our Time.’ Images by Patina Maldives and Pamela Longobardi

“It isn’t just one place’s plastic. It’s everywhere. We’re all involved in it, and the ocean is moving it as a giant engine. Plastic is at the centre of climate change.” — Pamela Longobardi

Now, nearly 20 years later, Longobardi has repeated this process countless times and her studio in Atlanta, Georgia, is filled with too much salvaged plastic to count. Most recently, she spent 10 days collecting plastics by herself and in group clean-ups around the Fari Islands in the Maldives. She then sorted through what had been found and combined it with pieces from her studio to create an artwork of 1,000 bits of plastic mounted on a 9-foot-by-5-foot panel. The massive work, titled Ocean Archaeology of Our Time, is formed in the shape of a plant she saw on the island. “I want to highlight that there are other lifeforms all around us that contribute to our ability to stay alive, and the planet’s ability to stay alive, and celebrate these life forms that are overlooked,” she says. The sculptural work was unveiled in October 2023 at the resort Patina Maldives.

Courtney Mattison: Reflecting on the Fragility of Reefs

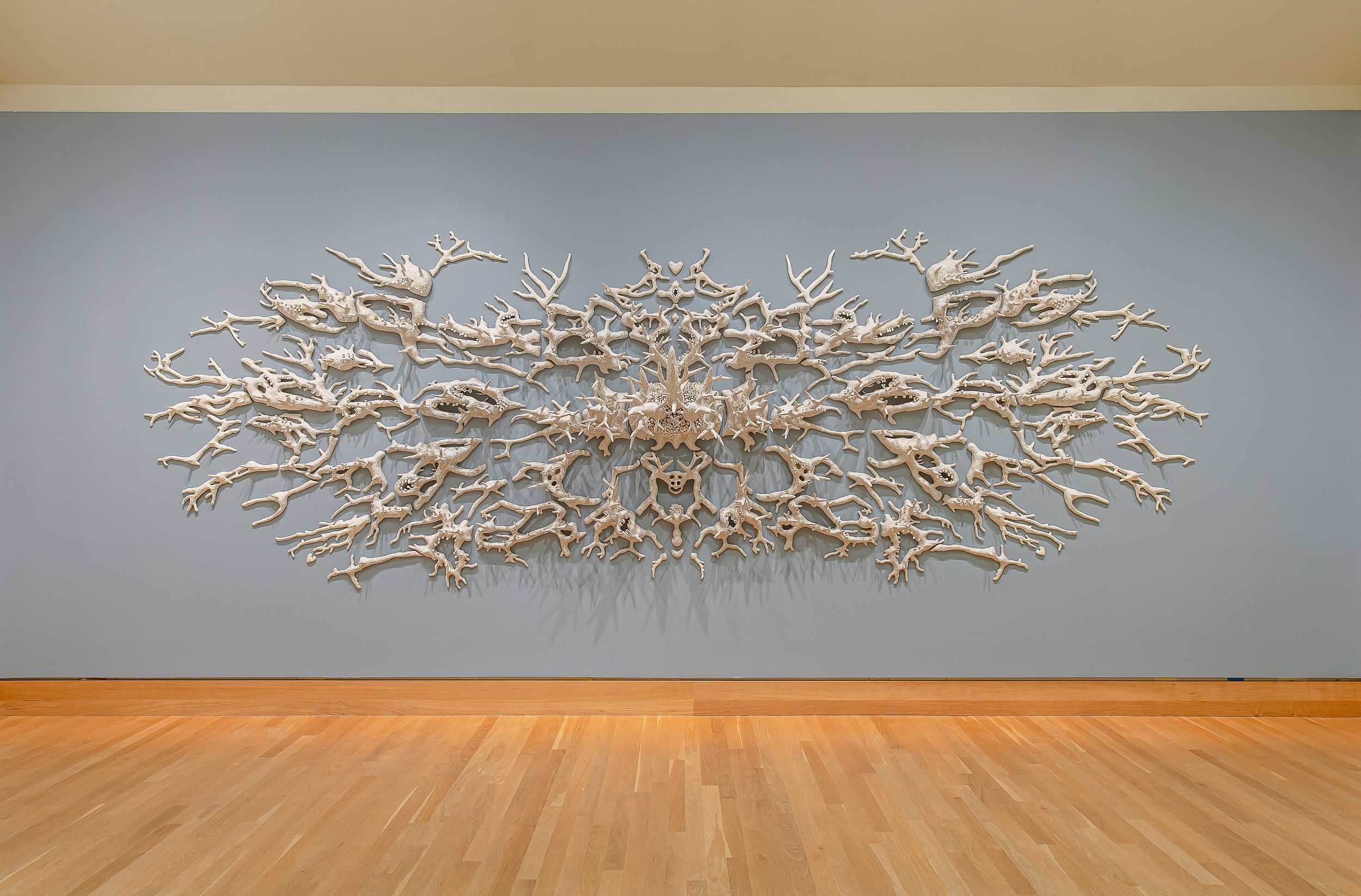

‘Confluence (Our Changing Seas V),’ 2017-2018, by Courtney Mattison. Image by Amanda Brooks

Courtney Mattison is a San Francisco-based artist and ocean advocate with a background in marine biology. For over 10 years, Mattison has been creating intricately detailed ceramic coral reefs installed in stunning swirls across walls. “I think of my work as building monuments to coral reefs in celebration of their beauty, their fragility and their value,” she says in an episode of Oceanic Society’s Blue Habits docuseries. At the heart of each work is a brightly coloured, healthy coral reef ecosystem; but as the installation spreads out across a wall, the individual ceramic pieces become paler and paler, until they appear in a uniform eggshell white, reflecting the devastating effects of climate change on reefs known as coral bleaching. Mattison was inspired to create such works at Australia’s Great Barrier Reef: “Seeing bleaching like that changed everything for me, because I could actually visualise climate change,” she told Oceanic Society. Since then, she has been bringing such visualisations to audiences around the world, above water. “I hope that [my works] will spark a sense of caring in viewers, enough to protect [the reefs],” she says.

“I think of my work as building monuments to coral reefs in celebration of their beauty, their fragility and their value” —Courtney Mattison

Artworks and images by Courtney Mattison

Tim Georgeson: Filmic Meditations Above and Below the Sea

Taking a different approach, Australian filmmaker and photographic artist Tim Georgeson addresses environmental issues through depictions of haunted landscapes. His 2019 film Mystic Sequence, for example, explores the connection between land and sea in Montauk, the storied, most eastern point of Long Island, New York. The camera zooms out slowly, high above land, and also goes deep below the surface of the water, capturing the sounds and sights from a bird’s eye view as well as from the perspective of sea creatures. The swirling visuals are overlaid with excerpts of Alan Watts — a British writer and speaker known for interpreting Buddhist, Taoist and Hindu philosophy for a Western audience — during a radio show segment titled Love of Waters. As the camera swims rhythmically through a bed of seaweed, Watts recites: “At our roots we are joined to the whole subject of nature. Of course, you may say that the nature of the universe is just a big abstraction. But tell me, is an orange just an abstraction from its component molecules?” With this work, Georgeson ruminates poetically on the fact that nothing in this world is an abstraction separate from its surroundings; everything and everyone is intertwined.

Image from Hidden Theatre (2021-2022) art installation by Tim Georgeson

Georgeson is also often in direct conversation with Indigenous artists and communities. His most recent project, Hidden Theatre (2021–22), comprises an installation of photographic, video and sound work created with the Indigenous Kalkadunga musician William Barton to examine both land and water. Together, they set out to explore the “hidden theatre” of the natural world surrounding the region of Bundanon, an area on the southeast coast of Australia. Georgeson’s images of the natural world — abstracted by his acute awareness of the power of light — are paired with Barton’s voice and the sounds of a didgeridoo, alluding to the ancient spirituality of the landscape and primordial knowledge systems from which we, and our planet, could benefit today.

Watch ‘Mystique Sequence’ (2019), Georgeson’s short film which explores the poetic connection between land and sea